Study Points

- Back to Course Home

- Participation Instructions

- Review the course material online or in print.

- Complete the course evaluation.

- Review your Transcript to view and print your Certificate of Completion. Your date of completion will be the date (Pacific Time) the course was electronically submitted for credit, with no exceptions. Partial credit is not available.

Study Points

Click on any objective to view test questions.

- Describe how the definition of palliative care has evolved.

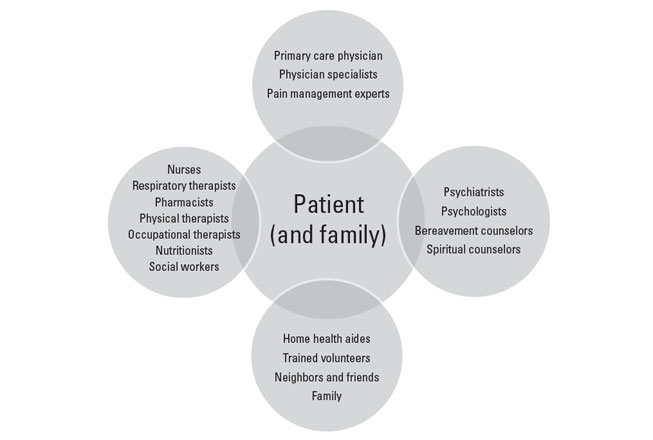

- Define the structure of palliative care delivery, including models of care and the interdisciplinary healthcare team.

- List the benefits of palliative care at the end of life.

- Anticipate the barriers to optimum delivery of palliative care through hospice.

- Effectively engage the components of communication and decision making for end-of-life care.

- Identify the common concerns and symptoms at the end of life for patients with life-limiting diseases.

- Discuss the barriers to effective relief of pain at the end of life.

- Assess pain accurately through use of clinical tools and other strategies.

- Select appropriate pharmacologic and/or non- pharmacologic therapies to manage pain in patients during the end-of-life period.

- Assess and manage the most common symptoms (other than pain) experienced by patients during the end-of-life period.

- Evaluate the psychosocial needs of patients at the end of life and their families and provide appropriate treatment or referral.

- Recognize and address the spiritual needs of patients at the end of life and provide appropriate treatment or referral.

- Develop a strategy for providing care to patients and their families over the last days and hours of life.

- Support appropriate grief and mourning.

- Explain the specific challenges and ethical considerations in delivering optimum palliative care to older patients, children, and patients in critical care settings.

Which of the following is TRUE about end-of-life care?

Click to ReviewThe term "palliative care" was first used by Balfour Mount, a Canada-trained physician and visiting professor at St. Christopher's Hospice, the first program of its kind. Dr. Mount subsequently established a palliative care program at Royal Victoria Hospital in Montreal, the first such program to be integrated in an academic teaching hospital [3]. Since that time, many attempts have been made to craft a definition of palliative care that represents its unique focus and goals. The challenge in defining palliative care has been encompassing all that such care refers to while specifying the timing of it (Table 1) [4,5,6,7,8]. The timing of palliative care remains an important point of discussion. As a result of its roots in hospice care, the term "palliative care" has often been considered to be synonymous with "end-of-life care." However, the current emphasis is to integrate palliative care earlier in the overall continuum of care (Figure 1) [6,9].

As the definition of palliative care has evolved, end-of-life care has become one aspect of palliative care. The time period assigned to "end of life" has not been defined, with the phrase being used to describe an individual's last months, weeks, days, or hours [10,11]. Designating a specific time period as the "end of life" is further challenged by disease trajectories that differ depending on the underlying life-limiting disease, a problem discussed in detail later in this course.

Which of the following is NOT a priority for patients with a life-limiting illness receiving palliative care?

Click to ReviewBecause palliative care focuses on the physical and psychosocial needs of the patient and his or her family, the patient's and family's perspectives are vital considerations in developing high-quality palliative care programs. An early survey of patients with life-limiting diseases identified five priorities for palliative care: receiving adequate treatment for pain and other symptoms, avoiding inappropriate prolongation of life, obtaining a sense of control, relieving burden, and strengthening relationships with loved ones [16]. In another study, a spectrum of individuals involved with end-of-life care (physicians, nurses, social workers, chaplains, hospice volunteers, patients, and recently bereaved family members) echoed these findings, with the following factors being noted as integral to a "good death:" pain and symptom management, clear decision making, preparation for death, completion, contributing to others, and affirmation of the whole person [17].

Which of the following is TRUE regarding the interdisciplinary healthcare team involved in palliative care?

The greatest increase in survival during hospice has been associated with which of the following diseases?

Click to ReviewThe most surprising finding is the apparent survival advantage conferred by palliative and hospice care. One study showed that hospice care extended survival for many patients within a population of 4,493 patients with one of five types of cancer (lung, breast, prostate, pancreatic, or colorectal cancer) or heart failure [51]. For the population as a whole, survival was a mean of 29 days longer for patients who had hospice care than for those who did not. With respect to the specific diseases, heart failure was associated with the greatest increase in survival (81 days), followed by lung cancer (39 days), colorectal cancer (33 days), and pancreatic cancer (21 days) [51]. There was no survival benefit for patients with breast or prostate cancer. In a study of patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer, patients who received early palliative care (within three weeks after enrollment in the study) lived significantly longer than those who received standard oncologic care only (11.6 months vs. 8.9 months) [30]. In the same study, the quality of life and symptoms of depression were also significantly better for the cohort of patients who received early palliative care. Similarly, a retrospective study found a slight survival advantage to hospice care among older individuals (>65 years) with advanced lung cancer [52]. These observations prompted the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) to publish a Provisional Clinical Opinion in which it states that concurrent palliative care and standard oncologic care should be offered to people with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer at the time of initial diagnosis [53]. The ASCO Opinion also notes that although the evidence of survival benefit is not as strong for other types of cancer, the same approach should be considered for any patient with metastatic cancer and/or high symptom burden [53]. The 2013 American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) guideline for the diagnosis and management of lung cancer also recommends that "palliative care combined with standard oncology care be introduced early in the treatment course" for patients with late-stage (i.e., stage IV) lung cancer and/or a high symptom burden [54].

Which of the following is NOT a barrier to the optimum use of palliative care at the end of life?

Click to ReviewAmong the most important barriers to the optimum use of palliative care at the end of life are the lack of well-trained healthcare professionals; reimbursement policies; difficulty in determining accurate prognoses; and attitudes of patients, families, and clinicians.

Which of the following is TRUE regarding the Medicare hospice benefit?

Click to ReviewMedicare reimbursement for hospice care became available when the Medicare Hospice Benefit was established in 1982, and reimbursement through private health insurances soon followed [34]. Reimbursement for hospice enabled more people with life-limiting disease to receive palliative care at home and in hospice units: the number of hospices in the United States has increased steadily, from 158 Medicare-certified hospices in 1985 to 4,639 in 2018 [1]. Despite the positive impact of the Medicare Hospice Benefit, fewer than half of eligible Medicare beneficiaries use hospice care and most only for a short period of time. This is because Medicare beneficiaries are required to forgo Medicare payment for care related to their terminal condition in order to receive access to Medicare hospice services (Table 4) [34,85]. The eligibility requirements of the benefit explicitly state that the focus of hospice "is on caring, not on curing," and in order to receive reimbursement for hospice services, patients must sign a statement that they will forego curative treatment [34]. This requirement frightens some patients or their families, who subsequently view hospice as "giving up." Furthermore, the restriction does not account for palliative treatments that serve the dual purpose of alleviating symptoms while prolonging life. For example, therapeutic regimens and measures designed to optimally treat heart failure are the same as those used for palliative care of patients with heart failure [76]. At present, there are no Medicare regulations that specify which treatments are considered palliative, and this lack of clarity has led to variation in what treatments individual hospice programs offer. Hospice care may be denied to patients receiving palliative chemotherapy or radiotherapy, and this may result in many people not choosing hospice. Although oncology experts have noted that radiotherapy is an important component of palliative care for many people with metastatic cancer, only 3% of people receiving hospice care receive radiation therapy; expense and the need to transport patients were the primary barriers [77,78,79]. Other palliative interventions, such as chemotherapy, blood transfusions, total parenteral nutrition, and intravenous medications, may not be economically feasible for small hospice units but may be possible at larger ones [80,81,82].

Many have suggested that the hospice model should change to allow for integration of disease-directed therapy [83,84]. The Affordable Care Act of 2010 stipulates that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) implement a three-year demonstration project to evaluate concurrent hospice care and disease-directed treatment [84]. This project represents a significant change to the eligibility criteria and, while the change has the potential to improve access to hospice care, careful assessment of the effect of concurrent treatment on use of hospice as well as on quality of life, quality of care, survival, and costs is needed [84]. Phase 2 of the project, the Medicare Care Choices Model (MCCM), became a six-year study (2016–2021) to assess whether offering Medicare beneficiaries the option to receive supportive, palliative care services through hospice providers without forgoing Medicare payments for treatment of their terminal conditions would improve beneficiaries' quality of life, increase their satisfaction with care, and reduce Medicare expenditures. In all, 89 of141 (63%) Medicare-certified hospices participated in MCCM; however, only 44 (31%) participated for all six years [85].

The Medicare Hospice Benefit criterion of a life expectancy of six months or less has also affected the timeliness of referral to hospice because of the aforementioned challenges in predicting prognosis. Many hospices were accused of fraud and were assessed financial penalties when government review found documentation of patients who received hospice care for longer than six months. As a result, many clinicians delayed hospice referral because of their lack of confidence in their ability to predict survival within six months. However, the six-month regulation has been revised, and a penalty is no longer assessed if a patient lives beyond six months if the disease runs its normal course [34].

Which of the following is TRUE regarding prognostication for life-limiting illnesses?

Click to ReviewTo make appropriate referrals to hospice, clinicians must be able to determine accurate prognoses, at least within the six-month timeframe required for reimbursement. However, prognostication is a complex issue and is a primary barrier to hospice use [88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95]. Studies have found that physicians typically overestimate survival, and one study found that physicians overestimate prognosis both in determining it and in communicating it to the patient [93,96,97]. The difficulty in determining the risk of death within a specific time period not only affects the ability of clinicians to make appropriate referrals to hospice but also impedes the ability of patients and families to make necessary end-of-life decisions, with many patients not fully understanding the severity and progressive nature of the disease [98].

Several factors contribute to physicians' difficulty in prognostication, including a desire to meet the patient's needs (for a cure or prolongation of life) and a lack of reliable prognostic models [81,97,99]. Perhaps the most important factor contributing to prognostic difficulty is the variations in disease trajectories, which have been characterized as a short period of evident decline, long-term limitations with intermittent serious episodes, and a prolonged decline (Figure 5) [9,32,100].

How difficult it is to determine a prognosis depends on the disease trajectory. Determining a prognosis in the cancer setting was once clear-cut because of the short period of evident decline, but advances in cancer therapies have made it more difficult to estimate a prognosis. Studies have shown rates of accurate prognosis of 20%, with survival usually overestimated, up to a factor of five [93,96]. The unpredictable course of organ-failure diseases, with its long-term limitations and acute exacerbations has always made prognostication difficult [62,89,101,102]. In a survey of cardiologists, geriatricians, and internists/family practitioners, approximately 16% of respondents said they could predict death from heart failure "most of the time" or "always" [89]. Predicting survival for people with the third type of trajectory (prolonged decline) is extremely difficult because of the wide variation in progressive decline. The prognosis for dementia can range from 2 to 15 years, and the end-stage may last for 2 years or more [103,104].

Which of the following is a clinician-related factor that contributes to the low rate of end-of-life discussions?

Click to ReviewSeveral patient-related and clinician-related factors contribute to the low rate of end-of-life discussions or their untimeliness. Most patients will not raise the issue for many reasons: they believe the physician should raise the topic without prompting, they do not want to take up clinical time with the conversation, they prefer to focus on living rather than death, and they are uncertain about continuity of care and fear abandonment [62,117,148,150]. Clinician-related factors include [81,147,148,160,161]:

Lack of time for discussion and/or to address patient's emotional needs

Uncertainty about prognosis

Fear about the patient's reaction (anger, despair, fear)

Lack of awareness and inability to elicit the concerns of patients and their families regarding prognosis

Lack of strategies to cope with own emotions and those of patient and family

Feeling of hopelessness or inadequacy about the lack of curative therapies (perceived as "giving up")

Which of the following is TRUE regarding the discussion of palliative treatment options and goals?

Click to ReviewTreatment options and goals of care are other topics that are often avoided in the end-of-life setting. A discussion of the survival benefit of palliative chemotherapy is frequently vague or absent from discussions of treatment options for patients with cancer [176]. In another example, approximately 60% to 95% of physicians involved with the care of patients with heart failure have two or fewer conversations about deactivation of implantable cardioverter defibrillators, and the discussions are usually within the last few days of life [89,177].

Deciding when curative therapy should end is difficult because of the advances made in treatment and life-prolonging technology and the unpredictable course of disease, especially for organ-failure diseases. These factors have led many patients, as well as some clinicians, to have unrealistic expectations for survival [30,178]. Unrealistic expectations are a major contributor to an increased use of aggressive treatment at the end of life. Among more than 900 patients with cancer, those who thought they would live for at least six months were more likely to choose curative therapy than "comfort care" compared with patients who thought there was at least a 10% chance they would not survive for six months [179].

Which of the following is TRUE regarding advance directives?

Click to ReviewAdvance directives, designation of a healthcare proxy, do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders, and living wills were developed as a way to ensure that patients received care that was consistent with their preferences and goals. Advance directives offer many benefits; they have been associated with a lower likelihood of in-hospital deaths, an increased use of hospice, and a significant reduction in costs [195]. Although early studies showed that advance directives did not always translate into patients receiving their preferred level of care, later studies have demonstrated that most patients with advance directives do receive care consistent with their preferences, especially if they want limited care (rather than "all possible" care) [194,196].

The American College of Physicians recommends that clinicians ensure that patients with "serious illness" engage in advance care planning, including the completion of advance directives [47]. Clinicians must emphasize the value of advance directives because most patients have not completed them. An estimated 20% of the population have written advance directives, with higher rates among the older population and nursing home residents and lower rates among minority populations and those with nonmalignant life-limiting diseases (compared with people with cancer) [197,198,199,200,201]. Other guidelines recommend that advance care planning be done early in the course of disease, to help avoid potential compromise of decision-making capacity near the end of life [62,108,121,122].

In preparing for a discussion about advance directives, clinicians should ask the patient if he or she wishes to have other family members present during the conversation. This is especially important for patients of some cultural backgrounds, as healthcare decisions are the responsibility of family members in many cultures [200]. Increased efforts should be aimed at obtaining advance directives from patients of minority races/ethnicities. Although the rate of advance directives is higher in the gay and lesbian community than in the general population, clinicians should emphasize the importance of these documents to gay and lesbian patients to ensure that the patient's wishes are carried out and to avoid legal consequences for the patient's partner [202].

Evidence-based guidelines for palliative care interventions are available from the American College of Physicians for which of the following symptoms?

Click to ReviewIn the wake of such studies, the American College of Physicians published a clinical practice guideline on palliative care interventions for three symptoms with the overall strongest evidence—pain, dyspnea, and depression—and evidence-based guidelines and recommendations for palliative care have been developed for respiratory diseases, heart failure, and end-stage renal disease [47,108,121,122,212,213,214]. These guidelines represent an important step toward enhancing palliative care, but more work is needed in many disease settings to address all aspects of palliative care. For one, definitions in palliative and supportive care are not standardized and remain a significant barrier to improvement [215].

Which of the following offers the best approach for the assessment of physical symptoms?

Click to ReviewAlthough asking open-ended questions about symptoms is helpful, systematic assessment of symptoms is also necessary. A study of patients in a palliative medicine program demonstrated that significantly more symptoms were identified on systematic assessment than through open-ended questioning (2,075 symptoms compared with 325) [221]. The symptoms that went unreported were not inconsequential; of those symptoms not initially volunteered by the patient, 69% were rated as "severe" and 79% were described as "distressing" [221]. Studies have demonstrated that patients are often reluctant to report worsening symptoms because of fear that they indicate progressive disease. Clinicians should describe potential symptoms to help patients and family understand which symptoms can be expected and when it is appropriate to notify a member of the healthcare team. It is important for the healthcare team to acknowledge the patient's symptoms as real and to take prompt actions to relieve them adequately. The patient's comfort should take precedence over the exact cause of the symptom. Diagnostic studies to determine the cause of symptoms should be undertaken only if the results will substantially help in directing effective treatment. The risks, benefits, costs, and options for treating an underlying cause should be discussed with the patient and family and considered within the context of the patient's culture, belief system, and expectations.

A patient's fear to take opioids might be related to a belief that

Click to ReviewThe inadequate management of pain is the result of several factors related to both patients and clinicians. In a survey of oncologists, patient reluctance to take opioids or to report pain were two of the most important barriers to effective pain relief [226]. This reluctance is related to a variety of attitudes and beliefs [222,226]:

Fear of addiction to opioids

Worry that if pain is treated early, there will be no options for treatment of future pain

Anxiety about unpleasant side effects from pain medications

Fear that increasing pain means that the disease is getting worse

Desire to be a "good" patient

Concern about the high cost of medications

Which of the following is FALSE regarding practitioner liability in pain management?

Click to ReviewFear of license suspension for inappropriate prescribing of controlled substances is also prevalent, and a better understanding of pain medication will enable physicians to prescribe accurately, alleviating concern about regulatory oversight. Physicians must balance a fine line; on one side, strict federal regulations regarding the prescription of schedule II opioids (morphine, oxycodone, methadone, hydromorphone) raise fear of Drug Enforcement Administration investigation, criminal charges, and civil lawsuits [222,232]. Careful documentation on the patient's medical record regarding the rationale for opioid treatment is essential [232]. On the other side, clinicians must adhere to the American Medical Association's Code of Ethics, which states that failure to treat pain is unethical. The code states, in part: "Physicians have an obligation to relieve pain and suffering and to promote the dignity and autonomy of dying patients in their care. This includes providing effective palliative treatment even though it may foreseeably hasten death" [233]. In addition, the American Medical Association Statement on End-of-Life Care requires that physicians "reassure the patient and/or surrogate that all other medically appropriate care will be provided, including aggressive palliative care and appropriate symptom management, if that is what the patient wishes" [234].

Physicians should consider the legal ramifications of inadequate pain management and understand the liability risks associated with both inadequate treatment and treatment in excess. The undertreatment of pain carries a risk of malpractice liability, and this risk is set to increase as the general population becomes better educated about the availability of effective approaches to pain management at the end of life. Establishing malpractice requires evidence of breach of duty and proof of injury and damages. Before the development of various guidelines for pain management, it was difficult to establish a breach of duty, as this principle is defined by nonadherence to the standard of care in a designated specialty. With such standards now in existence, expert medical testimony can be used to demonstrate that a practitioner did not meet established standards of care for pain management. Another change in the analysis of malpractice liability involves injury and damages. Because pain management can be considered as separate from disease treatment and because untreated pain can lead to long-term physical and emotional damage, claims can be made for pain and suffering alone, without wrongful death or some other harm to the patient [235].

Which of the following is TRUE regarding end-of-life care for patients with a history of substance abuse?

Click to ReviewThe population of people with a history of substance abuse presents challenges to the effective use of pain medication, with issues related to trust, the appropriate use of pain medications, interactions between illicit drugs and treatment, and compliance with treatment. The issues differ depending on whether substance abuse is a current or past behavior.

With active substance abusers, it is difficult to know if patients' self-reports of pain are valid or are drug-seeking behaviors. It has been recommended that, as with other patients at the end of life, self-reports of pain should be believed [67,227]. A multidisciplinary approach, involving15 psychiatric professionals, addiction specialists, and, perhaps, a pain specialist, is necessary. To decrease the potential for the patient to seek illicit drugs for pain, an appropriate pain management plan should be implemented, and the patient should be reassured that pain can be managed effectively [67,227]. When planning treatment, the patient's tolerance should be considered; higher doses may be needed initially, and doses can be reduced once acute pain is under control. Long-acting pain medications are preferred for active substance abusers, and the use of nonopioids and co-analgesics can help minimize the use of opioids. Setting limits as well as realistic goals is essential and requires establishing trust and rapport with the patient and caregivers.

Establishing trust is also essential for patients with former substance abuse behavior, who often must be encouraged to adhere to a pain management program because of their fears of addiction. Involving the patient's drug counselor is beneficial, and other psychological clinicians may be helpful in assuring the patient that pain can be relieved without addiction. Recurrence of addiction is low, especially among people with cancer, but monitoring for signs of renewed abuse should be ongoing [227].

Which of the following is the most reliable indicator of pain?

Click to ReviewPain should be assessed routinely, and frequent assessment has become the standard of care [223]. Pain is a subjective experience, and multidimensional in nature, and although patients' self-reporting of pain does not always correlate with objective functional measures, the patient's self-report of pain is the most reliable indicator [239,240]. Research has shown that pain is underestimated by healthcare professionals and overestimated by family members [223,241]. Therefore, it is essential to obtain a pain history directly from the patient, when possible, as a first step toward determining the cause of the pain and selecting appropriate treatment strategies. When the patient is unable to communicate verbally, other strategies should be used to determine the characteristics of the pain, as will be discussed.

Referred pain is usually an indicator of

Click to ReviewQuestions should be asked to elicit descriptions of the pain characteristics, including its location, distribution, quality, temporal aspect, and intensity. In addition, the patient should be asked about aggravating or alleviating factors. Pain is often felt in more than one area, and physicians should attempt to discern if the pain is focal, multifocal, or generalized. Focal or multifocal pain usually indicates an underlying tissue injury or lesion, whereas generalized pain could be associated with damage to the central nervous system. Pain can also be referred, usually an indicator of visceral pain.

Strong evidence supports pain management approaches for people with which of the following life-limiting diseases?

Click to ReviewStrong evidence supports pain management approaches for people with cancer, but the evidence base for management of pain in people with other life-limiting diseases is weak [47,54,108,187,212,214]. Effective pain management involves a multidimensional approach involving pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions that are individualized to the patient's specific situation [223].

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) ladder, pain should be managed

Click to ReviewThe WHO analgesic ladder, introduced in 1986 and disseminated worldwide, remains recognized as a useful educational tool but not as a strict protocol for the treatment of pain. It is intended to be used only as a general guide to pain management [245]. The three-step analgesic ladder designates the type of analgesic agent based on the severity of pain (Figure 6) [245]. Step 1 of the WHO ladder involves the use of nonopioid analgesics, with or without an adjuvant (co-analgesic) agent, for mild pain (pain that is rated 1 to 3 on a 10-point scale). Step 2 treatment, recommended for moderate pain (score of 4 to 6), calls for a weak opioid, which may be used in combination with a step 1 nonopioid analgesic for unrelieved pain. Step 3 treatment is reserved for severe pain (score of 7 to 10) or pain that persists after Step 2 treatment. Strong opioids are the optimum choice of drug at Step 3. At any step, nonopioids and/or adjuvant drugs may be helpful. Some consider this model to be outdated and/or simplistic, but most agree that it remains foundational. It can be modified or revised, as needed, to apply more accurately to different patient populations.

Which of the following is TRUE regarding pain medications?

Click to ReviewStrong opioids are used for severe pain (Step 3). Guidelines suggest that the most appropriate opioid dose is the dose required to relieve the patient's pain throughout the dosing interval without causing unmanageable side effects [187,206,246]. Morphine, buprenorphine, oxycodone, hydromorphone, fentanyl, and methadone are the most widely used Step 3 opioids in the United States. Unlike nonopioids, opioids do not have a ceiling effect, and the dose can be titrated until pain is relieved or side effects become unmanageable. For an opioid-naïve patient or a patient who has been receiving low doses of a weak opioid, the initial dose of a Step 3 opioid should be low, and, if pain persists, the dose may be titrated up daily until pain is controlled. Opioid-naïve patients are those who are not receiving opioid analgesic daily and therefore have not developed significant tolerance. Opioid-tolerant patients are those who have been taking an opioid analgesic daily for at least one week. The FDA identifies tolerance as receiving at least 60 mg of morphine daily, 30 mg of oral oxycodone daily, 8 mg of oral hydromorphone daily, or an equianalgesic dose of another opioid for one week or longer [187]. Typical starting doses for patients who are opioid-naïve have been noted, but these doses should be used only as a guide, and the initial dose, as well as titrated dosing, should be done on an individual basis (Table 8).

More than one route of opioid administration will be needed by many patients during end-of-life care, but in general, opioids should be given orally, as this route is the most convenient and least expensive. The transdermal route is preferred to the parenteral route, although dosing with a transdermal patch is less flexible and so may not be appropriate for patients with unstable pain [223]. Intramuscular injections should be avoided because injections are painful, drug absorption is unreliable, and the time to peak concentration is long [223].

The use of methadone to relieve pain has increased substantially over the past few years, moving from a second-line or third-line drug to a first-line medication for severe pain in people with life-limiting diseases [254]. A systematic review showed that methadone had efficacy similar to that of morphine. However, the authors' conclusions were based on low-quality evidence. Other opioids (e.g., morphine, fentanyl) are easier to manage but may be more expensive than methadone in many economies [255]. Physicians must be well educated about the pharmacologic properties of methadone, as the risk for serious adverse events, including death, is high when the drug is not administered appropriately [255,256]. If the dose of methadone is increased too rapidly or administered too frequently, toxic accumulation of the drug can cause respiratory depression and death. Because of the unique nature of methadone, and its long and variable half-life, extreme care must be taken when titrating the drug, and frequent and careful evaluation of the patient is required. Practitioners are advised to consult with a pain or palliative care specialist if they are unfamiliar with methadone prescribing or if individual patient considerations necessitate rapid switching to or from methadone [187].

Which of the following is considered the first-line opioid for Step 3?

Click to ReviewMorphine is considered to be the first-line treatment for a Step 3 opioid [206]. Morphine is available in both immediate-release and sustained-release forms, and the latter form can enhance patient compliance. The sustained-release tablets should not be cut, crushed, or chewed, as this counteracts the sustained-release properties. Morphine should be avoided in patients with severe renal failure [214].

Which of the following is TRUE regarding the management of fatigue?

Click to ReviewLittle evidence is available to support guidelines for the management of fatigue during the end of life. Most of the research on nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic treatment options has been conducted with subjects receiving active cancer treatment or long-term follow-up care after cancer treatment. Fatigue in the palliative care setting is addressed specifically by the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) (all settings) and the NCCN (cancer setting) and is noted in guidelines for palliative care for advanced heart failure [108,187,279]. In addition, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality has addressed fatigue in the cancer setting, and systematic reviews have been done to help determine effective pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions [281,290,291,292,293]. Management of fatigue should include treatment of an underlying cause, if one can be identified, but symptomatic relief should also be provided (Figure 10) [108,187,279].

When medications are the underlying cause of the fatigue, nonessential medications should be discontinued, and changing medications or the time of dosing may reduce tiredness during the day. Appropriate management of infection, cachexia, depression, and insomnia may also help reduce fatigue [279,287]. The patient's life expectancy and preferences should be considered before carrying out treatment of an underlying cause [279]. Fatigue may provide a protective effect for patients in the last days or hours of life [279]. As such, the patient may be more comfortable without aggressive treatment of fatigue during that period [279].

Most patients will try to manage fatigue by resting and/or sleeping more often, and many healthcare professionals will also recommend this strategy. However, additional rest and/or sleep usually does not restore energy in patients who have fatigue related to a life-limiting disease; continued lack of exercise may even promote fatigue [279]. Regular aerobic exercise and strength training has been found to alleviate fatigue, although much of the research in this area has been conducted with cancer survivors [284]. For example, a meta-analysis (28 studies, 2,083 subjects) demonstrated a significant effect of exercise in the treatment of fatigue during and after cancer treatment [293]. An update to this review and meta-analysis supported the benefit of aerobic exercise for individuals with cancer-related fatigue and recommended further research to determine the optimal type, intensity, and timing of an exercise intervention [300]. Some small studies of fatigue have been done in the palliative care setting, and exercise was found to be beneficial [301,302,303].

When managing dyspnea in patients with terminal illness,

Click to ReviewThe American College of Physicians, the American Thoracic Society, the Canadian Thoracic Society (endorsed by the ACCP), and the NCCN have developed evidence-based guidelines for the management of dyspnea [47,54,122,213,309,310]. In addition, evidence-based recommendations for managing dyspnea in people with advanced heart failure are available [108]. A stepwise approach to managing dyspnea should be taken, with the first step being treatment of the underlying cause, if one can be identified [54]. Nonpharmacologic interventions should be used first; if the response is inadequate, pharmacologic interventions may be added.

Supplemental oxygen is commonly used to treat dyspnea. Strong evidence supports the use of oxygen and pulmonary rehabilitation for dyspnea, and supplemental oxygen may provide relief of dyspnea for people with advanced lung or heart disease who have hypoxemia at rest or with minimal activity [47,54,212,213,309,310]. However, data suggest that oxygen offers no benefit to patients who do not have hypoxemia [108].

A variety of nonpharmacologic interventions have been suggested in several practice guidelines, although the evidence base varies (Table 13) [122,213,309,310]. In a systematic review of nonpharmacologic interventions and an update of that review for dyspnea in people with advanced malignant and nonmalignant diseases, there was strong evidence for chest wall vibration and neuroelectrical muscle stimulation and moderate evidence for walking aids and breathing training [311,312]. The updated review found low strength of evidence for acupuncture/acupressure, no evidence for the use of music, and insufficient evidence to recommend the use of a fan, music, relaxation, counseling and support, and psychotherapy [311,312]. A subsequent small randomized controlled trial demonstrated that a handheld fan directed at the face reduced breathlessness [313].

Opioids represent the primary recommended pharmacologic intervention for intractable dyspnea in people with advanced cancer and lung disease [47,213,309]. A systematic review and meta-analysis (18 randomized controlled trials) demonstrated a significant positive effect of opioids on breathlessness [315]. Guidelines recommend that oral or parenteral opioids be considered for all patients with severe and unrelieved dyspnea; nebulized opioids have not had an effect when compared with placebo [47,212,213,309]. Oral morphine is the most commonly prescribed opioid, but other opioids, such as diamorphine, dihydrocodeine, fentanyl, hydromorphone, and oxycodone, may be used [213]. The dose should be selected and titrated according to such factors as renal, hepatic, and pulmonary function and past use of opioids [213]. An oral dose of morphine of 2.5–10 mg every four hours as needed (1–5 mg intravenously) has been recommended for opioid-naïve patients [122]. Although respiratory depression is a side effect associated with opioids, especially morphine, this effect has not been found with doses used to relieve dyspnea [122,316]. Evidence-based recommendations for palliative care for people with heart failure note that diuretics represent the cornerstone of treatment of dyspnea [108]. Nitrates may also provide relief, and inotropes may be appropriate in select patients [108]. The recommendations also include the use of low-dose opioids [108].

Which of the following is TRUE regarding constipation in the end of life?

Click to ReviewIssues of personal privacy often lead to a reluctance of patients to discuss constipation, so clinicians and other healthcare professionals must initiate the discussion and talk honestly about what to expect and measures to prevent and manage the symptom. The assessment tools used most often are the Bristol Stool Form Scale and the Constipation Assessment Scale [319,320]. Assessment should include a review of the list of medications, a history of bowel habits, and abdominal and rectal examination. In addition to checking the list of prescribed medications to determine if constipation is a side effect, the physician should ask the patient about over-the-counter drugs and herbal remedies, as constipation can be a consequence of aluminum-containing antacids, ibuprofen, iron supplements, antidiarrhea drugs, antihistamines, mulberry, and flax. A detailed history of bowel habits helps to establish what is considered normal for the individual patient. The patient should be asked about frequency of stool, the appearance and consistency of stools, use of bowel medications, and previous occurrence of constipation. In general, physical examination of the abdomen for tenderness, distention, and bowel sounds can rule out intestinal obstruction as the cause of constipation. A rectal examination can identify the presence of stool, fecal impaction, or tumor. Imaging of the abdomen (by plain x-ray or computerized tomography) may be appropriate to confirm the presence of obstruction. Consideration of the patient's prognosis and preferences for care should be factored into a decision to carry out diagnostic testing. As with assessment of all symptoms, constipation should be reassessed frequently; assessment at least every three days is recommended [320].

Many laxatives are FDA approved for occasional constipation, and much of the evidence on their efficacy has come from studies of chronic constipation, not patients with life-limiting disease. In its guidelines for the management of chronic constipation, the American College of Gastroenterology notes the following [323]:

Polyethylene glycol (PEG) and lactulose (both osmotic) improve stool frequency and stool consistency.

Data are insufficient to make a recommendation about the efficacy of stool softeners (docusate [Colace or Surfak]); stimulant laxatives (senna [Senokot, Ex-Lax] or bisacodyl [Dulcolax, Correctol]); milk of magnesia; herbal supplements (aloe); lubricants (mineral oil); or combination laxatives (psyllium plus senna).

Which of the following antiemetic agents is recommended for uremia-induced nausea in people with end-stage chronic kidney disease?

Click to ReviewThe prokinetic agent metoclopramide (Reglan) has been recommended as a first-line treatment because of its central and peripheral actions and its effectiveness for many chemical and undetermined causes of nausea [206,246,328,331]. The drug should be used with caution in patients with heart failure, diabetes, and kidney or liver disease; the dose should be reduced by 50% for older patients and those with moderate-to-severe renal impairment [329,331]. Chronic use of prokinetic agents and dopamine receptor antagonists may be associated with the development of tardive dyskinesia, especially in frail, elderly patients [187]. Octreotide (Sandostatin), dexamethasone, and hyoscine hydrobromide (Scopolamine) are recommended for bowel obstruction [92,328,329,331,332]. Ondansetron (Zofran) has been suggested for chronic nausea, but in September 2011, the FDA issued a safety announcement about the drug, noting that it may increase the risk of QT prolongation on electrocardiogram. [329,335]. In 2012, the FDA updated the safety information specifically for the 32-mg IV dose of the drug, and the manufacturer subsequently announced changes to the drug label removing this dose [336]. Haloperidol (Haldol) is recommended for uremia-induced nausea in people with end-stage chronic kidney disease [214]. Dexamethasone is used for nausea and vomiting related to increased intracranial pressure and, although the evidence is limited, it is also used as second-line treatment for intractable nausea and vomiting and as an adjuvant antiemetic [246,328,329]. Olanzapine (Zyprexa), an atypical antipsychotic, has also been effective for nausea that has been resistant to other traditional antiemetics, as well as for opioid-induced nausea [337]. A benzodiazepine (such as lorazepam [Ativan]) may be of benefit if anxiety is thought to be contributing to nausea or vomiting [329].

The most widely used appetite enhancer for patients with life-limiting disease is

Click to ReviewTwo drugs are FDA approved as appetite stimulants for anorexia associated with life-limiting disease (Table 17). Megestrol acetate is FDA approved for the treatment of anorexia, cachexia, or unexplained weight loss in patients with AIDS [351]. It has become the most widely used drug for these indications for people with other life-limiting diseases, and a meta-analysis of data from studies (involving people with a variety of life-limiting illnesses) demonstrated that megestrol acetate was beneficial, especially with respect to improving appetite and weight gain in people with cancer [351]. Meta-analysis showed a benefit of megestrol acetate compared with placebo, particularly with regard to appetite improvement and weight gain in cancer, AIDS, and other underlying conditions. There was insufficient information to define the optimal dose, but higher doses were more related to weight improvement than lower doses. Side effects (e.g., edema, thromboembolic phenomena) and deaths were more frequent in patients treated with megestrol acetate compared with placebo [351]. Today, use of megestrol is limited due to the increased risk for thromboembolism. Dronabinol (Marinol), an oral cannabinoid, is FDA approved for anorexia associated with weight loss in people with AIDS [326]. Because of its effects, dronabinol should be used with caution for people with cardiac disorders, depression, or a history of substance abuse; people taking concomitant sedatives or hypnotics; and older individuals [326].

Among terminally ill patients, the highest rates of diarrhea have been associated with

Click to ReviewThe prevalence of diarrhea among adults with life-limiting disease varies widely, ranging from 3% to 90%, with the highest rates reported among people with HIV infection or AIDS [211].

The most common contributor to sleep disturbances in patients at the end of life is

Click to ReviewThe primary difference between insomnia in the general population and in people with life-limiting diseases is that insomnia in the latter group is usually secondary to the life-limiting disease or its symptoms [366]. Overall, uncontrolled pain is the most common contributor to the inability to sleep well [366,367]. Other common physical symptoms such as dyspnea, nocturnal hypoxia, nausea and vomiting, pruritus, and hot flashes are also causes of insomnia. Restless legs syndrome may be a substantial contributor to the disruption of sleep among persons with end-stage renal disease [210,310,368,369].

Which of the following is NOT a precipitating factor of delirium at the end of life?

Click to ReviewBecause of the substantial influence of unrelieved pain, adequate pain management can help prevent delirium. Prevention strategies are directed at minimizing precipitating factors, which include a high number of medications (more than six), dehydration, decreased sensory input, psychotropic medications, and a change in environment.

Of the following, which has been shown to be bothersome to the greatest proportion of individuals receiving palliative care?

Click to ReviewThe term "distress" has become standard to describe the psychological suffering experienced by patients with life-limiting disease. The NCCN notes that the word "distress" is more acceptable and is associated with less stigma than words such as "psychosocial" or "emotional" [396]. In its guidelines on distress management, the NCCN defines distress as existing "along a continuum, ranging from common normal feelings of vulnerability, sadness, and fears to problems that can become disabling, such as depression, anxiety, panic, social isolation, and existential and spiritual crisis" [396]. According to a study of patients in a palliative care program, the answers to the question "What bothers you most?" included [216]:

Emotional, spiritual, existential, or nonspecific distress (16%)

Relationships (15%)

Concerns about the dying process and death (15%)

Loss of function and normalcy (12%)

Which of the following is TRUE regarding anxiety at the end of life?

Click to ReviewOne of the primary causes of anxiety is inadequate pain relief. Anxiety may also be the result of a patient's overwhelming concern about his or her illness, the burden of the illness on the family, and the prospect of death. In addition, anxiety is a potential side effect of many medications, including corticosteroids, metoclopramide, theophylline, albuterol, antihypertensives, neuroleptics, psychostimulants, antiparkinsonian medications, and anticholinergics. Lastly, withdrawal from opiates, alcohol, caffeine, cannabis, and sedatives can result in anxiety, particularly in the first few days of admission [404].

Anxiety manifests itself through physical as well as psychological and cognitive signs and symptoms. These signs and symptoms include dyspnea, paresthesia, tachycardia, chest pain, urinary frequency, pallor, restlessness, agitation, hyperventilation, insomnia, tremors, excessive worrying, and difficulty concentrating.

Nonpharmacologic approaches are essential for managing anxiety, and the addition of pharmacologic treatment depends on the severity of the anxiety [67,407]. Effective management of pain and other distressing symptoms, such as constipation, dyspnea, and nausea, will also help to relieve anxiety. If the anxiety is thought to be caused by medications, they should be replaced by alternate drugs. Other strategies include psychological support that allows the patient to explore fears and concerns and to discuss practical issues with appropriate healthcare team members. Relaxation and guided imagery may also be of benefit [408]. A consult for psychological therapy may be needed for patients with severe anxiety.

Which of the following is FALSE regarding depression at the end of life?

Click to ReviewUnrelieved pain is one of the primary risk factors for depression. Other causes within the physical domain include metabolic disorders (hyponatremia or hypercalcemia), lesions in the brain, insomnia, or side effects of medications (corticosteroids or opioids). Many patients with heart failure have comorbidities and polypharmacy, both of which can increase the risk of depression [412,413]. Psychosocial causes include despair about progressive physical impairment and loss of independence, financial stress, family concerns, lack of social support, and spiritual distress.

A diagnosis of depression requires the presence of at least five depression-related symptoms within the same two-week period, and the symptoms must represent a change from a previous level of functioning [378]. A simple screening tool that has been found to be effective is to ask the patient, "Are you depressed?" or, "Do you feel depressed most of the time?" [227,414,415]. The physician should also discuss the patient's mood and behavior with other members of the healthcare team and family to help determine a diagnosis. Patients who have thoughts of suicide must be assessed carefully. The physician should differentiate between depression and a desire to hasten death because of uncontrolled symptoms [67]. Psychological counseling should be sought, as well as measures to enhance the management of symptoms.

The effective management of depression requires a multimodal approach, incorporating supportive psychotherapy, cognitive strategies, behavioral techniques, and antidepressant medications [47]. Patients with depression should be referred to mental health services for evaluation, and resultant approaches may include formal therapy sessions with psychiatrists or psychologists or counseling from social workers or pastoral advisors. In addition, physicians can help by having discussions with the patient to enhance his or her understanding of the disease, treatments, and outcomes, and to explore expectations, fears, and goals. Behavioral interventions, such as relaxation techniques, distraction therapy, and pleasant imagery have been effective for patients with mild-to-moderate depression [47].

Which of the following is FALSE regarding spiritual needs of patients at the end of life?

Click to ReviewMedical ethicists define spirituality as the ways people live in relation to transcendent questions of meaning, value, and relationship, whereas religion involves a community of beliefs and practices sharing a common orientation toward these spiritual questions [530]. Spirituality is unique to each person. It is founded in cultural, religious, and family traditions and is modified by life experiences. Spirituality is considered not to be dependent upon formal religious faith, and many surveys have shown that spirituality or religion is an integral component of people's lives [67,417]. Spirituality also plays a significant role in health and illness. Studies have shown spirituality to be the greatest factor in protecting against end-of-life distress and to have a positive effect on a patient's sense of meaning [411,418]. Thus, a spiritual assessment and spiritual care to address individual needs are essential components of the multidimensional evaluation of the patient and family [206,419].

Which of the following measures are appropriate for managing the so-called "death rattle?"

Click to ReviewAnticholinergic medications can eliminate the so-called "death rattle" brought on by the build-up of secretions when the gag reflex is lost or swallowing is difficult. However, it is important to note that results of clinical trials examining various pharmacologic agents for the treatment of death rattle have so far been inconclusive [432]. Despite the lack of clear evidence, pharmacologic therapies continue to be used frequently in clinical practice [430]. Specific drugs used include scopolamine, glycopyrrolate, hyoscyamine, and atropine (Table 25) [67,430,433]. Glycopyrrolate may be preferred because it is less likely to penetrate the central nervous system and with fewer adverse effects than with other antimuscarinic agents, which can worsen delirium [430]. For patients with advanced kidney disease, the dose of glycopyrrolate should be reduced 50% (because evidence indicates that the drug accumulates in renal impairment) and hyoscine butylbromide should not be used (because of a risk of excessive drowsiness or paradoxical agitation) [214]. Some evidence suggests that treatment is more effective when given earlier; however, if the patient is alert, the dryness of the mouth and throat caused by these medications can be distressful. Repositioning the patient to one side or the other or in the semiprone position may reduce the sound. Oropharyngeal suctioning is not only often ineffective but also may disturb the patient or cause further distress for the family. Therefore, it is not recommended.

Palliative sedation should

Click to ReviewPalliative sedation may be considered when an imminently dying patient is experiencing suffering (physical, psychological, and/or spiritual) that is refractory to the best palliative care efforts. Terminal restlessness and dyspnea have been the most common indications for palliative sedation, and thiopental and midazolam are the typical sedatives used [310,434,435]. For patients who have advanced kidney disease, midazolam is recommended, but the dose should be reduced because more unbound drug becomes available [214,310]. Before beginning palliative sedation, the clinician should consult with a psychiatrist and pastoral services (if appropriate) and talk to the patient, family members, and other members of the healthcare team about the medical, emotional, and ethical issues surrounding the decision [67,227,310,436,437]. Formal informed consent should be obtained from the patient or from the healthcare proxy.

Which of the following is considered to be physician-assisted death?

Click to ReviewPhysician-assisted death, or hastened death, is defined as active euthanasia (direct administration of a lethal agent with a merciful intent) or assisted suicide (aiding a patient in ending his or her life at the request of the patient) [67]. The following are not considered to be physician-assisted death: carrying out a patient's wishes to refuse treatment, withdrawal of treatment, and the use of high-dose opioids with the intent to relieve pain. The American Medical Association Code of Ethics explicitly states, "Physician-assisted suicide is fundamentally incompatible with the physician's role as healer, would be difficult or impossible to control, and would pose serious societal risks" [438]. Position statements against the use of physician-assisted death have been issued by many other professional organizations, including the NHPCO and the AAHPM [439,440]. The AAHPM states that their position is one of "studied neutrality" [439]. The basis for these declarations is that appropriate hospice care is an effective choice for providing comfort to dying patients.

Which of the following is TRUE regarding grief, mourning, and bereavement?

Click to ReviewGrief counseling for the family and patient should begin when the patient is alive, with a focus on life meaning and the contributions from the patient's family. An understanding of the mediators of the grief response can help physicians and other members of the healthcare team recognize the family members who may be at increased risk for adapting poorly to the loss [443]. These mediators are:

Nature of attachment (how close and/or dependent the individual was with regard to the patient)

Mode of death (the suddenness of the death)

Historical antecedents (how the individual has handled loss in the past)

Personality variables (factors related to age, gender, ability to express feelings)

Social factors (availability of social support, involvement in ethnic and religious groups)

Changes and concurrent stressors (number of other stressors in the individual's life, coping styles)

Satisfactory adaptation to loss depends on "tasks" of mourning [443]. Previous research referred to "stages" of mourning, but the term "task" is now used because the stages were not clear-cut and were not always followed in the same order. The tasks include:

Accepting the reality of the loss

Experiencing the pain of the loss

Adjusting to the environment in which the deceased is missing (external, internal, and spiritual adjustments)

Finding a way to remember the deceased while moving forward with life

After the patient's death, members of the palliative care team should encourage the family to talk about the patient, as this promotes acceptance of the death. Explaining that a wide range of emotions is normal during the mourning process can help family members understand that experiencing these emotions is a necessary aspect of grieving. Frequent contact with family members after the loved one's death can ensure that the family is adjusting to the loss. Referrals for psychosocial and spiritual interventions should be made as early as possible to optimize their efficacy.

Bereavement support should begin immediately with a handwritten condolence note from the clinician. Such notes have been found to provide comfort to the family [444,445]. The physician should emphasize the personal strengths of the family that will help them cope with the loss and should offer help with specific issues. Attendance at the patient's funeral, if possible, is also appropriate.

How bereavement services are provided through a hospice/palliative care program vary. Programs usually involve contacting the family at regular intervals to provide resources on grieving, coping strategies, professional services, and support groups [227,310]. When notes are sent, family members should be invited to contact the physician or other members of the healthcare team with questions. Notes are especially beneficial at the time of the first holidays without the patient, significant days for the family (patient's birthday, spouse's birthday), and the anniversary of the patient's death. Bereavement services should extend for at least one year after the patient's death, but a longer period may be necessary [6,227].

The issue of perhaps greatest importance regarding palliative care for older individuals is improving care for patients

Click to ReviewPerhaps the greatest issue is the need for better palliative care for patients with dementia [103,448,464]. The prevalence of dementia has been reported to be 40% to 50% among persons older than 80 years of age, and many persons with dementia spend the last weeks to months of life in a nursing home [465]. Underlying dementia makes it difficult to identify symptoms, especially pain and psychosocial disorders. As a result, suffering is prevalent among patients with dementia. In fact, one study showed that 93% of patients with dementia died with an intermediate or high level of suffering [466]. The assessment of pain can be particularly challenging when the patient is unable to communicate. This situation calls for a multipronged approach consisting of observation, discussion with family and caregivers, and evaluation of the response to pain medication or nonpharmacologic measures. Recommendations for assessing pain in nonverbal patients have been developed by the American Society for Pain Management Nursing [467].

Which of the following is TRUE regarding end-of-life care for children?

Click to ReviewThe involvement of the young patient in discussions about diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment goals is another important issue in the pediatric population. Members of the healthcare team should collaborate with parents to determine how much information should be shared with the child and how involved the child should be with decision making; these determinations should be based on the child's intellectual and emotional maturity [14,484]. Many parents wish to protect their child by withholding information, but studies have shown that children often recognize the seriousness of their illness and prefer open communication about their disease and prognosis [485,486]. Such open exchange of information can help to avoid the fear of the unknown and preserve the child's trust in his or her parents and/or family and caregivers [486]. Thus, as much as possible and appropriate, the child should be allowed to participate in discussions about the direction of care [484].

According to reports of parents, the most common symptoms during the last month of life are similar to those among adults; fatigue (weakness) and pain have been the most frequently reported (Table 27) [481,490,491]. When evaluating fatigue in children, age is a consideration in how fatigue is discussed. Children think about fatigue as a physical sensation, and adolescents think about fatigue as either physical and/or mental tiredness [492]. Parents or other caregivers tend to report fatigue in terms of how it interferes with the child's activities [492].

Pain management according to the WHO ladder has been found to be effective for children/adolescents [502,503,504,505]. The main components of the WHO strategy include [504,505]:

Using the oral form of medication whenever possible

Dosing analgesics at regular intervals

Administering analgesics based on the severity of pain assessed using a pain-intensity scale

Tailoring medication dosing to the individual patient

Monitoring the patient carefully throughout the prescription of pain medications

Acetaminophen or NSAIDs, codeine, or oxycodone is recommended for pain rated as 0–3 on a scale of 0 to 10; an acetaminophen/opioid combination, NSAIDs, oxycodone, or morphine is recommended for pain rated as 4–6; and morphine or oxycodone is recommended for pain rated as 7–10 [187]. It is important to note that codeine may not be metabolized in 35% of children, and analgesia will be ineffective in those children [187]. Pharmacokinetic data for pediatric medications are lacking, and physicians should consult pediatric specialists for appropriate dosing of medications for symptom relief. Pain medication should be complemented by age-appropriate nonpharmacologic interventions; touch, massage, stroking, and rocking are effective for infants, toddlers, and young children, and guided imagery, music and art therapy, play therapy, controlled breathing, and relaxation techniques are beneficial for older children [493,506,507].

Attention to psychosocial support for the patient, parents, and other family members is crucial in the pediatric setting. Although most parents think that psychosocial issues should be discussed with the child's physician and would find that discussion to be valuable, fewer than half of parents raise such topics [508]. Furthermore, parents report that only 15% to 20% of physicians assess the family's psychosocial issues [508]. Among the psychosocial issues common in children/adolescents and their families are ineffective family coping strategies, the patient's relationships with peers, psychological adjustment of healthy siblings, and long-term psychological adjustment for parents [484,506,509,510,511,512,513]. The palliative care team must carefully evaluate the patient and family and provide resources and appropriate referrals.

In end-of-life care for critically ill patients,

Click to ReviewNearly 50% of patients who die in the hospital are in the ICU for some period of time during the last three days of life [514,515]. In addition, 13% of patients admitted to the ICU with traumatic injury will die [514]. The abruptness of a traumatic injury is vastly different from the illness trajectories of life-limiting diseases, and palliative care seems incongruous in the ICU, a high-technology environment of the most aggressive life-prolonging treatments. The effective delivery of palliative care is challenged by many factors inherent in the ICU setting, including inadequate training of healthcare professionals, unrealistic expectations of patients and families, misunderstanding of lifesaving measures, and a greater need for surrogate decision making [514,516,517]. As these factors gain greater recognition, there is a growing emphasis on integrating palliative care elements into the care of patients with traumatic injury and/or patients in an ICU [122,514,516,517,518,519].

The focus on complex, lifesaving care in the ICU creates a gap in providing relief of patients' symptoms. As in all settings, symptom assessment and management should be a priority for ICU patients. It has been suggested that an interdisciplinary palliative care assessment be carried out early in an ICU stay, preferably within 24 hours after admission, with documentation of a comprehensive care plan within 72 hours after admission [517,520].

ICU patients are often young, and families expect lifesaving procedures to be effective [517]. Misunderstanding of lifesaving measures has been reported to be an obstacle to high-quality palliative care [521]. Clinicians and other members of the team should maintain open, ongoing communication about the patient's prognosis, the feasibility of recovery, and the burden of treatment. The sudden, often catastrophic events that bring patients to the ICU compound stress and grief in family members, whose psychosocial needs peak earlier than in other palliative care settings [517]. As a result, psychosocial and bereavement support for families must begin early in the course of the patient's stay in the ICU, preferably within 24 hours after the patient's admission to the ICU [517].

The abruptness of traumatic injury or catastrophic illness is also associated with the lack of preparation of advance directives for many patients. There is often no time for planning during the short end-of-life process, and approximately 95% of patients are unable to participate in their care [517]. As a consequence, surrogates must make decisions, and such decisions have been shown to correlate poorly with the preferences of patients [522,523].

- Back to Course Home

- Participation Instructions

- Review the course material online or in print.

- Complete the course evaluation.

- Review your Transcript to view and print your Certificate of Completion. Your date of completion will be the date (Pacific Time) the course was electronically submitted for credit, with no exceptions. Partial credit is not available.