This course is designed to bridge the gap in knowledge of palliative care by providing an overview of the concept of palliative care and a discussion of the benefits and barriers to optimum palliative care at the end of life. Central to this discussion is an emphasis on the importance of talking to patients about the value of palliative care, of clearly presenting the prognosis and appropriate treatment options and goals, and of ensuring that advance planning is completed. The majority of the course focuses on the assessment and management of the most common end-of-life symptoms, with particular attention to pain, the most prevalent, as well as the most distressing, physical symptom. Psychosocial and spiritual needs of the patient and family are also discussed. Palliative care presents unique challenges for some patient populations, most notably older patients, children/adolescents, and patients receiving critical care. An overview of the most important issues specific to these settings is provided.

This course is designed for all members of the interprofessional team, including physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, pharmacy technicians, social workers, marriage and family therapists, and other members seeking to enhance their knowledge of palliative care.

The purpose of this course is to provide an overview of the concept of palliative care as distinct from hospice care, including a discussion of challenges, benefits, and strategies for optimal palliative care and symptom management at the end of life.

Upon completion of this course, you should be able to:

- Define palliative care, including benefits, delivery, and possible barriers to effective use.

- Describe the most common symptoms experienced by patients during the end-of-life period.

- Analyze the psychosocial and spiritual needs of patients near the end of life, including special populations.

John M. Leonard, MD, Professor of Medicine Emeritus, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, completed his post-graduate clinical training at the Yale and Vanderbilt University Medical Centers before joining the Vanderbilt faculty in 1974. He is a clinician-educator and for many years served as director of residency training and student educational programs for the Vanderbilt University Department of Medicine. Over a career span of 40 years, Dr. Leonard conducted an active practice of general internal medicine and an inpatient consulting practice of infectious diseases.

Contributing faculty, John M. Leonard, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationship with any product manufacturer or service provider mentioned.

John V. Jurica, MD, MPH

Mary Franks, MSN, APRN, FNP-C

Alice Yick Flanagan, PhD, MSW

Margaret Donohue, PhD

Randall L. Allen, PharmD

The division planners have disclosed no relevant financial relationship with any product manufacturer or service provider mentioned.

Sarah Campbell

The Director of Development and Academic Affairs has disclosed no relevant financial relationship with any product manufacturer or service provider mentioned.

The purpose of NetCE is to provide challenging curricula to assist healthcare professionals to raise their levels of expertise while fulfilling their continuing education requirements, thereby improving the quality of healthcare.

Our contributing faculty members have taken care to ensure that the information and recommendations are accurate and compatible with the standards generally accepted at the time of publication. The publisher disclaims any liability, loss or damage incurred as a consequence, directly or indirectly, of the use and application of any of the contents. Participants are cautioned about the potential risk of using limited knowledge when integrating new techniques into practice.

It is the policy of NetCE not to accept commercial support. Furthermore, commercial interests are prohibited from distributing or providing access to this activity to learners.

Supported browsers for Windows include Microsoft Internet Explorer 9.0 and up, Mozilla Firefox 3.0 and up, Opera 9.0 and up, and Google Chrome. Supported browsers for Macintosh include Safari, Mozilla Firefox 3.0 and up, Opera 9.0 and up, and Google Chrome. Other operating systems and browsers that include complete implementations of ECMAScript edition 3 and CSS 2.0 may work, but are not supported. Supported browsers must utilize the TLS encryption protocol v1.1 or v1.2 in order to connect to pages that require a secured HTTPS connection. TLS v1.0 is not supported.

The role of implicit biases on healthcare outcomes has become a concern, as there is some evidence that implicit biases contribute to health disparities, professionals' attitudes toward and interactions with patients, quality of care, diagnoses, and treatment decisions. This may produce differences in help-seeking, diagnoses, and ultimately treatments and interventions. Implicit biases may also unwittingly produce professional behaviors, attitudes, and interactions that reduce patients' trust and comfort with their provider, leading to earlier termination of visits and/or reduced adherence and follow-up. Disadvantaged groups are marginalized in the healthcare system and vulnerable on multiple levels; health professionals' implicit biases can further exacerbate these existing disadvantages.

Interventions or strategies designed to reduce implicit bias may be categorized as change-based or control-based. Change-based interventions focus on reducing or changing cognitive associations underlying implicit biases. These interventions might include challenging stereotypes. Conversely, control-based interventions involve reducing the effects of the implicit bias on the individual's behaviors. These strategies include increasing awareness of biased thoughts and responses. The two types of interventions are not mutually exclusive and may be used synergistically.

#97384: Palliative Care and Pain Management at the End of Life

The concept of palliative care has garnered much attention since the term was first used in the late 1960s to refer to a holistic approach to patient-centered care, with a focus on enhancing the quality of life for patients living with serious illness and their families. As currently practiced, palliative care is interdisciplinary team care designed to engage the expertise of providers from different clinical disciplines. The purpose of palliative care is to alleviate suffering and provide comfort; to this end, the primary goals are relief of pain and other distressing symptoms, effective communication with the patient and family in order to establish patient-centered goals of care, attentiveness to psychological and spiritual needs, and support for family members. With its roots in hospice care, the term "palliative care" has long been used interchangeably with "end-of-life care." However, in contrast to hospice, the initiation of palliative care is not contingent upon the expectation that the patient has less than six months to live or that disease-directed therapy has run its course. Across all specialties, the emphasis now is on the integration of palliative care into the ongoing management strategy for any patient with a serious, life-threatening illness, regardless of age. Hospice care is palliative care provided in the last weeks and months of life, when disease-directed or curative treatment has been exhausted or deemed no longer to be of benefit[1].

Palliative care at the end of life is delivered most effectively through hospice. Palliative care/hospice was once primarily confined to the cancer setting because of the evident and often rapid health decline to death with this disease. Hospice extended to the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) setting for the same reason. Ongoing advances in medicine have changed these once-lethal diseases into chronic conditions, shifting the trajectory of illness and leaving a growing number of patients in need of palliative care for longer periods of time. Similarly, individuals with other life-limiting diseases, such as heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), end-stage renal disease, and dementia, are in need of similar care. Thus, a growing number of individuals could benefit from palliative care. However, palliative/hospice care is underutilized in the United States for a variety of reasons, and many patients experience an unnecessary degree of physical and psychological suffering at the end of life [1,2].

Both clinician- and patient-related factors contribute to the underuse of palliative/hospice care. In addition, evidence-based guidelines are lacking for end-of-life care for many noncancer life-threatening conditions. More research on the prevalence and severity of symptoms and functional status in patients with life-limiting diseases, as well as the efficacy of interventions is needed to generate these much-needed guidelines.

This course is designed to bridge the gap in knowledge of palliative care by providing an overview of the concept of palliative care and associated clinical issues and a discussion of the benefits and barriers to optimum palliative care at the end of life. Central to this discussion is an emphasis on the importance of talking to patients about the value of palliative care, of clearly presenting the prognosis and appropriate treatment options and goals, and of ensuring that advance planning is completed. Much of the course focuses on the assessment and management of the most common end-of-life needs, with particular attention to pain, the most prevalent, as well as the most distressing, physical symptom. Psychosocial and spiritual needs of the patient and family are also discussed. Palliative care presents unique challenges for some patient populations, most notably older patients, children/adolescents, and patients receiving critical care. An overview of the most important issues specific to these settings is provided.

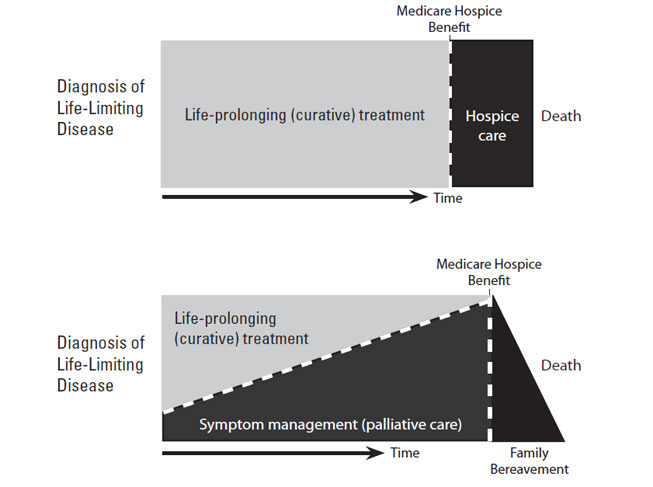

The term "palliative care" was first used by Balfour Mount, a Canada-trained physician and visiting professor at St. Christopher's Hospice, the first program of its kind. Dr. Mount subsequently established a palliative care program at Royal Victoria Hospital in Montreal, the first such program to be integrated in an academic teaching hospital [3]. Since that time, many attempts have been made to craft a definition of palliative care that represents its unique focus and goals. The challenge in defining palliative care has been encompassing all that such care refers to while specifying the timing of it (Table 1) [4,5,6,7,8]. The timing of palliative care remains an important point of discussion. As a result of its roots in hospice care, the term "palliative care" has often been considered to be synonymous with "end-of-life care." However, the current emphasis is to integrate palliative care earlier in the overall continuum of care (Figure 1) [6,9].

EVOLVING DEFINITION OF PALLIATIVE CARE

| Year | Source and Definition | Comments | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | World Health Organization (WHO): "…The active total care of patients whose disease is not responsive to curative treatment." | Does not apply exclusively to palliative care | ||

| 1993 | The Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine: "The study and management of patients with active, progressive, far-advanced disease for whom the prognosis is limited and the focus of care is the quality of life." | Lacks essential aspects, such as support provided to families, as well as specificity about timing | ||

| 2004 |

| First definition to reflect integration of palliative care earlier into the disease continuum | ||

| 2007 | WHO (revision): "An approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problem associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial, and spiritual." | Improvement over original WHO definition, but expansion of palliative care throughout the continuum of care not explicit | ||

| 2009 | American Society of Clinical Oncology: "Palliative cancer care is the integration into cancer care of therapies to address the multiple issues that cause suffering for patients and their families and have an impact on the quality of their lives. Palliative cancer care aims to give patients and their families the capacity to realize their full potential, when their cancer is curable as well as when the end of life is near." | Defines palliative care for patients with cancer, but definition can be applied to palliative care in all settings | ||

| 2013 | National Consensus Project: "Palliative care means patient and family-centered care that optimizes quality of life by anticipating, preventing, and treating suffering. Palliative care throughout the continuum of illness involves addressing physical, intellectual, emotional, social, and spiritual needs and to facilitate patient autonomy, access to information, and choice." | Characterization of palliative care in the United States, as defined by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the National Quality Forum |

As the definition of palliative care has evolved, end-of-life care has become one aspect of palliative care. The time period assigned to "end of life" has not been defined, with the phrase being used to describe an individual's last months, weeks, days, or hours [10,11]. Designating a specific time period as the "end of life" is further challenged by disease trajectories that differ depending on the underlying life-limiting disease, a problem discussed in detail later in this course.

Since the establishment of the first hospice in the United States in 1974, many initiatives have been undertaken to enhance the quality of care given at the end of life. The lack of progress in relieving end-of-life suffering was highlighted with the publication of findings from the Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment (SUPPORT) [12,13]. The results of this landmark study indicated that in-hospital deaths were characterized by prolonged suffering, uncontrolled pain, and caregiver hardship. In response, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) commissioned a report on the quality of care at the end of life, and the authors of this report, Approaching Death: Improving Care at the End of Life, noted that too many patients "suffer needlessly" at the end of life and emphasized the need for better training of healthcare professionals and reform of outdated laws that inhibited the use of pain-relieving drugs [2]. A subsequent IOM report pointed out the need for enhanced pediatric palliative care [14]. Several initiatives have been developed to address the deficiencies in the quality of palliative care; to optimize the use of hospice; to help the lay public better understand the meaning of palliative care and hospice and their benefits; and to enhance the knowledge, skills, and attitudes of healthcare professionals. Five organizations—the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine (AAHPM), the Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC), the Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association, the Last Acts Partnership, and the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO)—joined forces in the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care Consortium and published clinical practice guidelines to help reduce the variation in palliative care programs and enhance continuity of care across healthcare settings [6]. The National Quality Forum (NQF) built on these guidelines when it proposed a national framework for palliative and hospice care [15].

Other efforts included the first core curriculum in hospice and palliative care, created by the AAHPM; the development of the Education in Palliative and End-of-Life Care (EPEC) Project (https://www.bioethics.northwestern.edu/programs/epec); and the subsequent development of the EPEC-Oncology (EPEC-O) curriculum and the End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium Project (https://www.aacnnursing.org/ELNEC).

Because palliative care focuses on the physical and psychosocial needs of the patient and his or her family, the patient's and family's perspectives are vital considerations in developing high-quality palliative care programs. An early survey of patients with life-limiting diseases identified five priorities for palliative care: receiving adequate treatment for pain and other symptoms, avoiding inappropriate prolongation of life, obtaining a sense of control, relieving burden, and strengthening relationships with loved ones [16]. In another study, a spectrum of individuals involved with end-of-life care (physicians, nurses, social workers, chaplains, hospice volunteers, patients, and recently bereaved family members) echoed these findings, with the following factors being noted as integral to a "good death:" pain and symptom management, clear decision making, preparation for death, completion, contributing to others, and affirmation of the whole person [17].

The priorities set by patients and healthcare professionals were considered carefully in the structuring of clinical practice guidelines for high-quality palliative care developed by the National Consensus Project (NCP) for Quality Palliative Care. These guidelines are organized according to eight domains [6]:

Structure and processes of care

Physical aspects

Psychological and psychiatric aspects

Social aspects

Spiritual, religious, and existential aspects

Cultural aspects

Care of the patient nearing the end of life

Ethical and legal aspects

In its publication, the NQF sets forth 39 guidelines based on these eight domains (Table 2) [6].

GUIDELINES FOR PALLIATIVE AND HOSPICE CARE

|

Palliative care service is rendered through several different models, including hospital-based inpatient programs, outpatient clinics (based in hospitals or private practices), and combined consultation services and inpatient programs. Hospice programs may provide a consultative service but generally assume direct responsibility for end-of-life palliative care rendered at home, hospital, or other hospice resident facility [15]. The Joint Commission began offering an advanced certification program for palliative care in September 2011 [18]. In an effort to enhance access to end-of-life care, models of care are being adapted for a variety of specific settings, such as rural communities, correctional facilities, long-term care facilities, children's hospitals, and intensive care units [19,20,21,22,23,24].

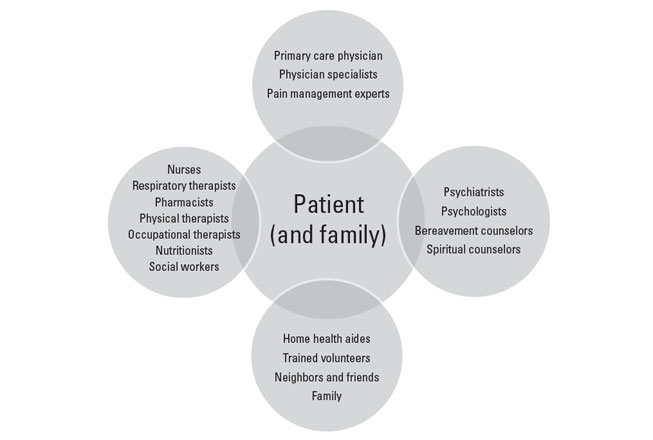

The delivery of comprehensive palliative care relies on a team of skilled providers with experience and training in the principles of palliative care (Figure 2). The team may be organized around a primary care clinician or a palliative care specialist who functions as consultant or principal provider [15,25,26,27]. Palliative care interventions have been shown to significantly improve patient outcomes, although the data are stronger for patients with cancer than for life-limiting diseases overall [28,29]. This is illustrated by results of a randomized controlled trial of early palliative care provided as an adjunct to standard oncologic care for patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. In this study, involving 151 subjects enrolled from a single academic practice, patients in the intervention group were seen by a palliative care clinician regularly (once or more per month) for 12 weeks; in comparison to the group receiving only standard care, the intervention (palliative care) group had a measurably better quality of life, lower rate of depression, and improved survival by 2.7 months [30].

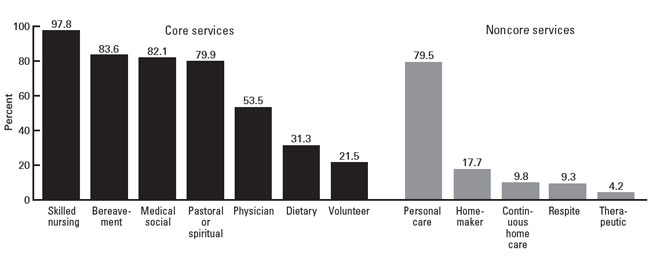

The composition of a hospice care team is essentially the same as for a standard palliative care team. The primary service provided during hospice care is skilled nursing care and management of distressing symptoms, followed by bereavement services and medical social services (Figure 3) [31]. Clinical specialists (e.g., oncologists, cardiologists, pulmonologists) also become members of a palliative care team when they are involved with the care of their patients during the end of life. Family physicians and general internists typically provide primary palliative care; this level of care requires skill in core palliative care competencies (such as basic symptom assessment and management and knowledge of psychosocial and community services) [6,8].

The composition of the healthcare team and the roles of its members may differ across palliative care settings, and roles and responsibilities should be clear and well documented to help members work effectively as a team. Team members' roles should also be communicated to the patient and the family.

The primary care physician is usually responsible for referral to palliative care through hospice when the patient has a non-cancer diagnosis. In general, the primary care physician becomes the attending physician, assuming primary responsibility for the patient [32,33]. The primary care physician should be prepared to relinquish some autonomy in order to work effectively with the interdisciplinary team [32]. Home-based hospice care is organized around a team that includes the attending physician, registered nurse, social worker, and counselor. These team members are necessary for Medicare reimbursement [34]. The attending physician collaborates with other members of the hospice team to manage symptoms and fulfills other basic obligations, such as admission orders, medication prescriptions and refills, certification of hospice eligibility, and signing of the death certificate [33].

High-quality palliative care also requires special expertise in honest, compassionate communication. In addition to enhancing the patient's and family's experience, these skills help to establish trust and overcome barriers to adequate care and relief of symptoms. Several communication tasks are especially important: conveying accurate prognostic information while maintaining hope, eliciting information about symptoms, decision making about curative and palliative treatments, handling emotions, and dealing with requests from patients and families who have unrealistic goals [35,36,37]. The challenges of communicating effectively are discussed later in this course.

Despite the increasing use of hospice, palliative care and hospice are underutilized services. The NHPCO statistics show the share of Medicare decedents who used hospice increased from 44.0% in 2010 to 51.6% in 2018; decreased to 47.3% in 2021, because of the COVID-19 pandemic; then increased to 49.1% in 2022 [1]. Hospice use varies according to several demographic factors. Patients treated in hospice are primarily women, although the gap has been closing, with 54.3% of the hospice population being female [1]. Studies show that White individuals are more likely to use hospice than are individuals in minority populations [38,39,40,41]. However, from 2018 to 2022, NHPCO data show that hospice utilization by Medicare decedents increased among all race/ethnicity groups surveyed. In 2022, 51.6% of White, 38.3% of Hispanic, 38.1% of Asian American, 37.4% of Black, and 37.1% of North American Native Medicare decedents were enrolled in hospice [1].

The lower rates of hospice use in minority populations have been attributed to many factors, including beliefs about health care, death, and end-of-life care; lack of awareness of hospice services; mistrust of the healthcare system; cultural differences in healthcare decision making and in disclosure of illness to the patient; lack of insurance; lack of healthcare professionals' cultural competency; lower referral rates by health care professionals; and the hospice caregiver requirement [40,42,43,44].

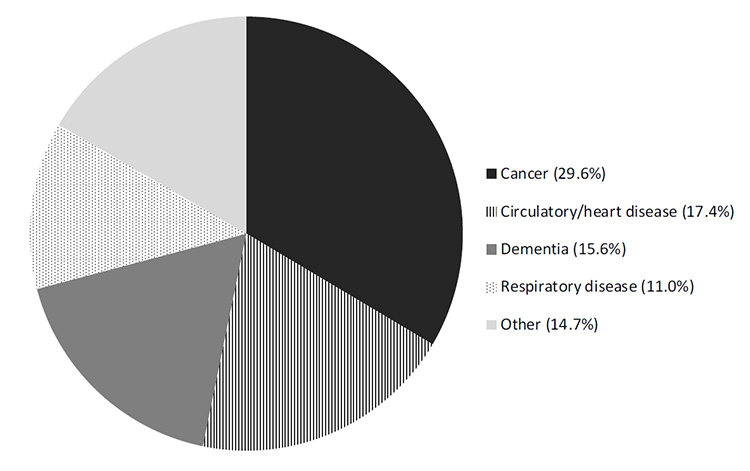

Cancer and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/AIDS were once the predominant diseases in hospice and palliative care programs, but as treatments for these diseases have improved, the number of individuals with the diseases in hospice programs has decreased while the number of individuals with chronic, progressive diseases has increased. In 2021, Alzheimer dementia/nervous system disorders/organic psychosis (25%), cancer (23%), and cardiac/circulatory system diseases (22%) were the three most common diagnoses (by ICD-10 code) in the hospice population, accounting for nearly three-quarters of all hospice beneficiary diagnoses (Figure 4) [1].

Most of the studies designed to determine the benefits of palliative care/hospice at the end of life have centered on patients with cancer. However, an increasing number of researchers are focusing on palliative care interventions for patients with other life-limiting diseases. The field of palliative care/hospice research has grown considerably in the past decade, but reliable meta-analyses of palliative care studies have been limited because of variations in methodology and in the focus and extent of services [45]. Increasingly, studies are confirming the benefits of palliative care/hospice in terms of quality of life, satisfaction with care, and end-of-life outcomes, as well as cost-effectiveness.

A systematic review indicated weak evidence of benefit for palliative care/hospice. The results did demonstrate significant benefit of specialized palliative care interventions in four of 13 studies in which quality of life was assessed and in one of 14 studies in which symptom management was assessed [29]. However, the authors of the review noted that most of the studies lacked the statistical power to provide conclusive results, and the quality-of-life measures evaluated were not specific for patients at the end of life [29]. Other research has shown that palliative care intervention was associated with significantly better quality of life and greater patient and/or family caregiver satisfaction [45,46,47]. Data to support benefit in reducing patients' physical and psychological symptoms have been lacking [45]. Such symptoms were significantly improved when patients received care delivered by palliative care specialists [28].

Surveys of patients' family members also demonstrate the value of palliative care. The Family Assessment of Treatment at the End of Life (FATE) survey was developed to evaluate family members' perceptions of their loved one's end-of-life care in the Veterans Administration (VA) healthcare system. FATE consists of nine domains: well-being and dignity, information and communication, respect for treatment preferences, emotional and spiritual support, management of symptoms, choice of inpatient facility, care around the time of death, access to VA services, and access to VA benefits after the patient's death. Using the assessment tool, researchers found that palliative care and hospice services were associated with significantly higher overall scores compared with usual care [48].

In addition to the benefits realized by patients, palliative care is beneficial for patients' family members as well. According to a survey of bereaved family members, a significantly higher proportion of respondents had their emotional or spiritual needs met when the patient received palliative care (compared with "usual care") [49]. Palliative care was also seen to improve family member coping skills and the ability to manage the inevitable tasks associated with terminal illness; that is, more family members knew what to expect when the patient was dying, felt competent to participate in the care of the dying person, and felt confident in knowing what to do when the patient died [49]. Other studies have shown benefit for caregivers through positive effects on caregiver burden, anxiety, satisfaction, and the ability to "move on" more easily after the patient's death [46,50].

The most surprising finding is the apparent survival advantage conferred by palliative and hospice care. One study showed that hospice care extended survival for many patients within a population of 4,493 patients with one of five types of cancer (lung, breast, prostate, pancreatic, or colorectal cancer) or heart failure [51]. For the population as a whole, survival was a mean of 29 days longer for patients who had hospice care than for those who did not. With respect to the specific diseases, heart failure was associated with the greatest increase in survival (81 days), followed by lung cancer (39 days), colorectal cancer (33 days), and pancreatic cancer (21 days) [51]. There was no survival benefit for patients with breast or prostate cancer. In a study of patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer, patients who received early palliative care (within three weeks after enrollment in the study) lived significantly longer than those who received standard oncologic care only (11.6 months vs. 8.9 months) [30]. In the same study, the quality of life and symptoms of depression were also significantly better for the cohort of patients who received early palliative care. Similarly, a retrospective study found a slight survival advantage to hospice care among older individuals (>65 years) with advanced lung cancer [52]. These observations prompted the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) to publish a Provisional Clinical Opinion in which it states that concurrent palliative care and standard oncologic care should be offered to people with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer at the time of initial diagnosis [53]. The ASCO Opinion also notes that although the evidence of survival benefit is not as strong for other types of cancer, the same approach should be considered for any patient with metastatic cancer and/or high symptom burden [53]. The 2013 American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) guideline for the diagnosis and management of lung cancer also recommends that "palliative care combined with standard oncology care be introduced early in the treatment course" for patients with late-stage (i.e., stage IV) lung cancer and/or a high symptom burden [54].

The cost of care at the end of life is a controversial issue because of the disproportionate costs incurred for care within the last two years of life and the wide variation in costs related to the aggressiveness of care across healthcare facilities [55]. The simple act of discussing end-of-life issues can help patients and families better understand options, leading to reduced costs. In a study of 603 patients with advanced cancer, costs in the last week of life were approximately $1,000 lower for patients who had end-of-life discussions with their healthcare providers compared with patients who did not have such conversations [56].

Several studies have documented the cost-effectiveness of hospice care. A meta-analysis published in 1996 showed that hospice care reduced healthcare costs by as much as 40% during the last month of life and 17% over the last six months [57]. A later study demonstrated little difference in costs at the end of life, with the exception of costs for patients with cancer, which were 13% to 20% lower for those who had received hospice care than for those who had not [58]. In a study of 298 patients with end-stage organ failure diseases, in-home hospice care significantly reduced healthcare costs by decreasing the number of hospitalizations and emergency department visits [46]. The strongest evidence of cost savings is found in a 2007 study in which hospice use reduced Medicare costs during the last year of life by an average of $2,309 per hospice user [59]. As was found earlier, the cost savings were greater for patients with cancer than for those with other diagnoses [59]. The greatest cost reduction (about $7,000) was associated with a primary diagnosis of cancer and length of stay of 58 to 103 days [59]. The maximum cost savings was much lower (approximately $3,500) for other life-limiting diagnoses but with a similar length of stay (50 to 108 days) [59].

Palliative care consultations also reduce costs. A review of data for Medicaid beneficiaries (with a variety of life-limiting diagnoses) at four hospitals in New York showed that hospital costs were an average of $6,900 lower during a given admission for patients who received palliative care than for those who received usual care [60]. The reduction in costs was greater ($7,563) for patients who died in the hospital compared with those who were discharged alive [60].

Despite the many benefits of palliative care and hospice, referrals are usually not timely and often are not made at all [61,62,63,64,65,66]. Many challenges contribute to the low rate of optimum end-of-life care.

Among the most important barriers to the optimum use of palliative care at the end of life are the lack of well-trained healthcare professionals; reimbursement policies; difficulty in determining accurate prognoses; and attitudes of patients, families, and clinicians.

Medical school and residency training programs emphasize disease recognition, diagnostic assessment, and treatment and management strategies that have restorative power, prolong life, and prevent death. The role of palliative care traditionally has not been sufficiently addressed [67]. Students who have participated in mandatory courses in palliative medicine have noted that they are better prepared to care for dying patients [68]. Efforts to enhance education have resulted in the development of more than 100 primary care residency programs that offer palliative medicine as part of the curriculum and 72 postgraduate medical fellowship programs in palliative care [69,70]. In addition, hospital-based palliative care programs have integrated the eight NCP domains into graduate courses and residencies for physicians and registered nurses, and certifications in palliative care have become available for physicians, nurses, and social workers [6]. Between 1996 and 2006, more than 2,100 physicians obtained certification in hospice and palliative medicine from the American Board of Hospice and Palliative Medicine [71]. As of January 2016, there were nearly 6,400 active certified hospice and palliative care physicians in the United States [72]. In 2006, subspecialty certification in hospice and palliative medicine was established for 10 Boards within the American Board of Medical Specialties. The first exam was held in 2008, and 1,274 physicians earned certification in hospice and palliative medicine. Since then, the number of physicians who have earned certification though the American Board of Medical Specialties has increased fivefold, with physicians in internal medicine and family medicine accounting for 85% of the total (Table 3) [73].

NUMBER OF PHYSICIANS CERTIFIED IN SUBSPECIALTY OF HOSPICE AND PALLIATIVE MEDICINE, 2014–2023

| American Board Specialty | No. of Physicians |

|---|---|

| Internal medicine | 4,167 |

| Family medicine | 1,573 |

| Pediatrics | 268 |

| Anesthesiology | 100 |

| Emergency medicine | 247 |

| Psychiatry and neurology | 119 |

| Surgery | 70 |

| Radiology | 60 |

| Obstetrics and gynecology | 71 |

| Physical medicine and rehabilitation | 29 |

| Total | 6,604 |

Initiatives to enhance the knowledge and skills of nurses have included graduate nursing programs in palliative care, instructional resources for nursing educators, communication skills training for nurses, and educational programs for home care professionals, as well national certifications [6,74]. More than 18,000 nurses are Board-certified in hospice and palliative nursing [75].

Medicare reimbursement for hospice care became available when the Medicare Hospice Benefit was established in 1982, and reimbursement through private health insurances soon followed [34]. Reimbursement for hospice enabled more people with life-limiting disease to receive palliative care at home and in hospice units: the number of hospices in the United States has increased steadily, from 158 Medicare-certified hospices in 1985 to 4,639 in 2018 [1]. Despite the positive impact of the Medicare Hospice Benefit, fewer than half of eligible Medicare beneficiaries use hospice care and most only for a short period of time. This is because Medicare beneficiaries are required to forgo Medicare payment for care related to their terminal condition in order to receive access to Medicare hospice services (Table 4) [34,85]. The eligibility requirements of the benefit explicitly state that the focus of hospice "is on caring, not on curing," and in order to receive reimbursement for hospice services, patients must sign a statement that they will forego curative treatment [34]. This requirement frightens some patients or their families, who subsequently view hospice as "giving up." Furthermore, the restriction does not account for palliative treatments that serve the dual purpose of alleviating symptoms while prolonging life. For example, therapeutic regimens and measures designed to optimally treat heart failure are the same as those used for palliative care of patients with heart failure [76]. At present, there are no Medicare regulations that specify which treatments are considered palliative, and this lack of clarity has led to variation in what treatments individual hospice programs offer. Hospice care may be denied to patients receiving palliative chemotherapy or radiotherapy, and this may result in many people not choosing hospice. Although oncology experts have noted that radiotherapy is an important component of palliative care for many people with metastatic cancer, only 3% of people receiving hospice care receive radiation therapy; expense and the need to transport patients were the primary barriers [77,78,79]. Other palliative interventions, such as chemotherapy, blood transfusions, total parenteral nutrition, and intravenous medications, may not be economically feasible for small hospice units but may be possible at larger ones [80,81,82].

MEDICARE HOSPICE BENEFIT

| Variables | Criteria | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benefits (covered services) |

| |||||

| Nonreimbursable services |

| |||||

| Period of care | Two 90-day periods, followed by unlimited number of 60-day periods | |||||

| Restrictions |

|

Many have suggested that the hospice model should change to allow for integration of disease-directed therapy [83,84]. The Affordable Care Act of 2010 stipulates that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) implement a three-year demonstration project to evaluate concurrent hospice care and disease-directed treatment [84]. This project represents a significant change to the eligibility criteria and, while the change has the potential to improve access to hospice care, careful assessment of the effect of concurrent treatment on use of hospice as well as on quality of life, quality of care, survival, and costs is needed [84]. Phase 2 of the project, the Medicare Care Choices Model (MCCM), became a six-year study (2016–2021) to assess whether offering Medicare beneficiaries the option to receive supportive, palliative care services through hospice providers without forgoing Medicare payments for treatment of their terminal conditions would improve beneficiaries' quality of life, increase their satisfaction with care, and reduce Medicare expenditures. In all, 89 of141 (63%) Medicare-certified hospices participated in MCCM; however, only 44 (31%) participated for all six years [85].

Of 7,253 Medicare beneficiaries who enrolled in the MCCM program, all qualified for hospice and met other eligibility criteria, including having cancer, heart failure, chronic pulmonary disease, or HIV/AIDS [85]. Enrollees received supportive and palliative care services through MCCM while continuing to receive Medicare coverage for disease-directed treatment of their terminal condition. Specific MCCM-directed services included assessment of health and health-related social needs, care coordination and case management, access to healthcare professionals, person- and family-centered care planning, shared decision-making, and management of symptoms. Length of enrollment varied (median: two months) and 89% of enrollees died before the end of the MCCM program. Surveyed MCCM enrollees and caregivers reported high levels of satisfaction with their quality of life, shared decisions, and receiving care consistent with individual wishes. MCCM enrollees had 12% fewer outpatient emergency department visits, 26% fewer inpatient admissions, and lower net Medicare expenditures when compared to a matched group of non-participants [85]. Deceased enrollees were less likely than comparison beneficiaries to receive aggressive life-prolonging treatment in the last 30 days of life and spent more days at home before death.

The Medicare Hospice Benefit criterion of a life expectancy of six months or less has also affected the timeliness of referral to hospice because of the aforementioned challenges in predicting prognosis. Many hospices were accused of fraud and were assessed financial penalties when government review found documentation of patients who received hospice care for longer than six months. As a result, many clinicians delayed hospice referral because of their lack of confidence in their ability to predict survival within six months. However, the six-month regulation has been revised, and a penalty is no longer assessed if a patient lives beyond six months if the disease runs its normal course [34].

Unfortunately, reimbursement for end-of-life care discussions is not as straightforward as for hospice care. An effort to establish government reimbursement for discussions of end-of-life care options, including hospice care and advance directives, sparked a political storm that led to the removal of the proposed reimbursement from the healthcare reform bill of 2011. However, beginning in January 2016, the CMS introduced two Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) reimbursement codes for advance care planning visits [86,87]. Despite a national increase in advance care planning claims, the overall claims rate remains low. Two-thirds of hospice and palliative medicine specialists did not use the new CPT codes in 2017, despite working with seriously ill patients [87].

To make appropriate referrals to hospice, clinicians must be able to determine accurate prognoses, at least within the six-month timeframe required for reimbursement. However, prognostication is a complex issue and is a primary barrier to hospice use [88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95]. Studies have found that physicians typically overestimate survival, and one study found that physicians overestimate prognosis both in determining it and in communicating it to the patient [93,96,97]. The difficulty in determining the risk of death within a specific time period not only affects the ability of clinicians to make appropriate referrals to hospice but also impedes the ability of patients and families to make necessary end-of-life decisions, with many patients not fully understanding the severity and progressive nature of the disease [98].

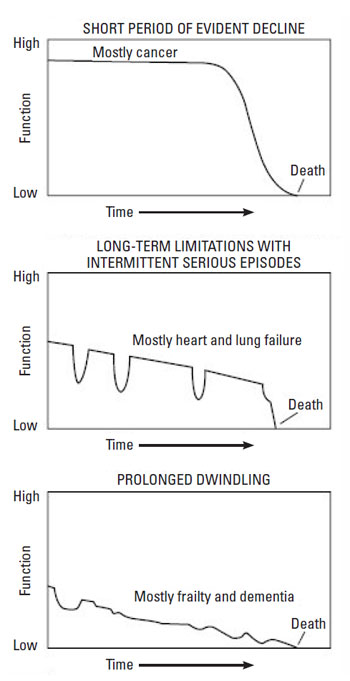

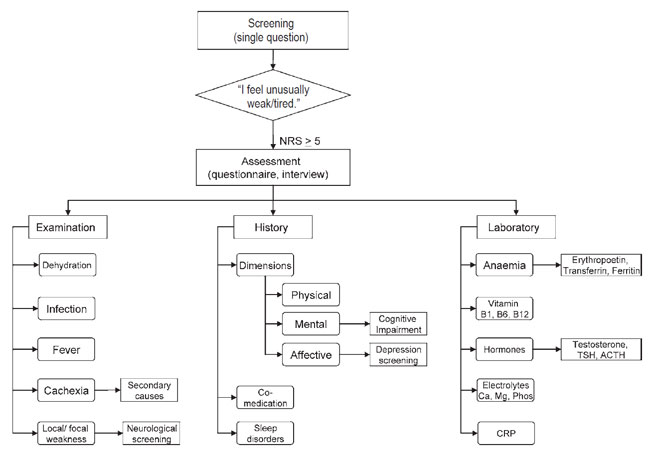

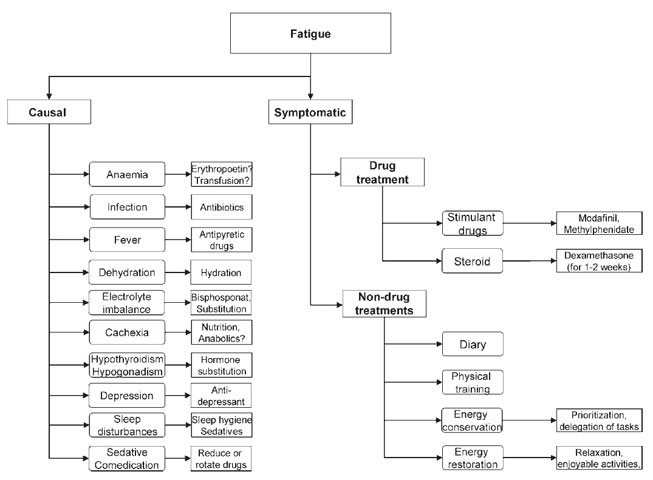

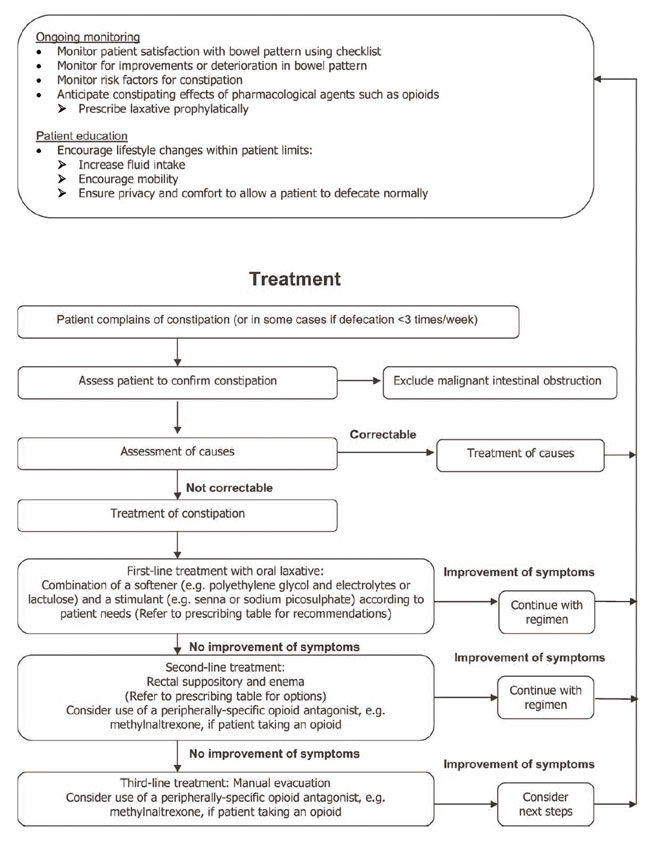

Several factors contribute to physicians' difficulty in prognostication, including a desire to meet the patient's needs (for a cure or prolongation of life) and a lack of reliable prognostic models [81,97,99]. Perhaps the most important factor contributing to prognostic difficulty is the variations in disease trajectories, which have been characterized as a short period of evident decline, long-term limitations with intermittent serious episodes, and a prolonged decline (Figure 5) [9,32,100].

How difficult it is to determine a prognosis depends on the disease trajectory. Determining a prognosis in the cancer setting was once clear-cut because of the short period of evident decline, but advances in cancer therapies have made it more difficult to estimate a prognosis. Studies have shown rates of accurate prognosis of 20%, with survival usually overestimated, up to a factor of five [93,96]. The unpredictable course of organ-failure diseases, with its long-term limitations and acute exacerbations has always made prognostication difficult [62,89,101,102]. In a survey of cardiologists, geriatricians, and internists/family practitioners, approximately 16% of respondents said they could predict death from heart failure "most of the time" or "always" [89]. Predicting survival for people with the third type of trajectory (prolonged decline) is extremely difficult because of the wide variation in progressive decline. The prognosis for dementia can range from 2 to 15 years, and the end-stage may last for 2 years or more [103,104].

To help facilitate more timely referrals to hospice, the NHPCO established guidelines for determining the need for hospice care, and these guidelines were adopted by the Health Care Finance Administration to determine eligibility for Medicare hospice benefits [76]. Other prognostic models have been developed, such as the SUPPORT model, the Palliative Prognostic (PaP) Score, and the Palliative Prognostic Index (PPI) [12,105,106,107]. Most were developed for use in the cancer setting and for hospitalized patients, and their value beyond those settings has not been validated [81,95]. In addition, the PaP and the PIP will identify most patients who are likely to die within weeks but are much less reliable for patients who have 6 to 12 months to live [95]. A systematic review showed that the NHPCO guidelines, as well as other generic and disease-specific prognostic models, were not adequately specific or sensitive to estimate survival of at least six months for older individuals with nonmalignant life-limiting disease, especially heart failure, COPD, and end-stage liver disease [99].

Most prognostic tools for organ-failure diseases are used to estimate the risk of dying and to select patients for treatment, not to determine when end-of-life care should be initiated. Several models have been established to determine prognosis for heart failure; the one used most often is the Seattle Heart Failure model, which represents the most comprehensive set of prognostic indicators to provide survival data for one, two, and five years [108,109]. Newer evidence-based recommendations for estimating survival in advanced cancer have been published, as has a nomogram; however, use of the nomogram for hospice referral is limited, as it estimates survival at 15, 30, and 60 days [81,110].

For estimating prognosis in advanced dementia—a condition with the most challenging disease trajectory—the Advanced Dementia Prognostic Tool (ADEPT) has been shown to be better than the NHPCO guidelines in identifying nursing home residents with advanced dementia at high risk of dying in six months [111]. However, the ability of ADEPT to identify these patients is modest [111]. Lastly, the Patient-Reported Outcome Mortality Prediction Tool (PROMPT) was developed to estimate six-month mortality for community-dwelling individuals 65 years or older with self-reported declining health over the past year; the model shows promise for making appropriate hospice referrals, but the model needs validation [112].

In addition to the low reliability of these models, another problem is that the clinician's prediction of survival remains integral, as it is one element in prognostic models, sometimes representing as much as half of a final score [110]. Other variables include performance status, laboratory data, and quality of life scales.

Researchers continue to evaluate prognostic variables to establish criteria for prognosis, especially disease-specific criteria. In its guidelines for palliative care, the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI) distinguished between the clinical indicators that should prompt palliative care discussions and those that should prompt hospice referral (Table 5) [113]. According to the ICSI, "all hospice is palliative care, but not all palliative care is hospice" [113].

COMPARISON BETWEEN PALLIATIVE CARE AND HOSPICE

| Condition | Palliative Carea | Hospiceb | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer |

| Any patient with metastatic or inoperable cancer | |||||||||

| Heart disease |

|

| |||||||||

| Pulmonary disease |

|

| |||||||||

| Dementia |

|

| |||||||||

| Liver disease |

|

| |||||||||

| Renal disease |

|

| |||||||||

| Neurologic disease |

|

| |||||||||

| |||||||||||

This difficulty in determining prognosis can have a negative impact on the appropriate timing of hospice referral and the degree of benefit to be derived. Although the use of hospice has increased over the past decades, the timing of referral has not changed significantly since the mid-1980s [114]. The average length of hospice care is much lower than the six months allowed by the Medicare benefit; in 2022, the average length was 95.3 days, and the median duration (a more accurate reflection because it is not influenced by outliers) was 18 days [1]. In addition, approximately 25% of patients died (or were discharged) within only five days [1]. Studies have indicated that the benefits of hospice increase as the duration of care increases, and such services as bereavement counseling, palliative care, and respite for caregivers is best when hospice care is provided for four to eight weeks, a longer period of time than the median stay [59,115].

Longer durations of hospice services are also linked to family members' perceptions of the quality of care. According to the findings of 106,514 surveys from 631 hospices in the United States, 11% of family members thought their loved one was referred "too late" to hospice; this perception was associated with more unmet needs, higher reported concerns, and lower satisfaction [116].

In contrast to the restrictions on access to hospice, there are no restrictions on access to palliative care. Referrals for palliative care should be made on the basis of actual or anticipated needs at any time during the disease continuum; referrals should not be made on the basis of prognostic models [81,99]. Referrals for specialist palliative care should be made when treatment goals change from curative to palliative [117,118]. A consensus report from the Center to Advance Palliative Care provides guidance for identifying patients with a life-limiting illness who are at high risk of unmet palliative care needs [118]. The report includes criteria for referral for palliative care assessment at the time of hospital admission and during each hospital day (Table 6) [118]. Experts in nonmalignant life-limiting diseases are calling for earlier palliative care consultation. Such consultation before implantation of a left ventricular assist device as destination therapy is recommended, as it has been shown to improve the quality of care and advance care planning [119,120]. Guidelines for renal and respiratory diseases note that all patients with these diseases should be offered palliative care services, and the integration of palliative care specialists into liver transplantation teams has been suggested [121,122,123].

CRITERIA FOR PALLIATIVE CARE ASSESSMENT AT THE TIME OF HOSPITAL ADMISSION AND DURING HOSPITAL STAY

| At Time of Hospital Admission | ||||||||||

| Primary criteriaa |

| |||||||||

| Secondary criteriab |

| |||||||||

| During Hospital Stay | ||||||||||

| Primary criteriaa |

| |||||||||

| Secondary criteriab |

| |||||||||

| ||||||||||

Physicians have reported that they delay discussions of palliative care and hospice because they fear the reaction of the patient and/or family [32,33]. Negative reactions are grounded in a lack of accurate knowledge about palliative care and hospice. According to two polls conducted in 2011 (800 adults in one poll and 1,000 adults in the other), 70% to 92% of respondents were not "too" or "at all" familiar with the term palliative care [124,125].

Enhancing the public's knowledge can improve access to palliative care: the 2011 polls showed that once palliative care was appropriately defined, 92% said they were likely (63% "very likely" and 29% "somewhat likely") to consider palliative care for a loved one who had a serious illness and 96% said that it was important for palliative (and end-of-life) care to be a top priority for the healthcare system [124,125].

Hospice is a more familiar concept to the general population. One of the polls showed that 86% of respondents were familiar with the term hospice care, and other studies have indicated that approximately half of patients with a life-limiting illness know what hospice is [125,126]. Although people may be familiar with the term, many believe several myths about hospice; for example, that hospice is only for old people, is only for people with cancer, is for people who do not need a high level of care, is used when there is no hope, and is expensive [127].

Several other factors contribute to negative feelings about hospice [80,88,128]:

Denial or lack of awareness about the severity of the illness

Not wanting to "give up"

Fear of abandonment by the family physician

Perception that the patient will not receive adequate medical services

Interpretation of hospice referral as a cost-savings measure

When initiating a discussion about palliative care and hospice, clinicians should always first ask the patient if he or she has heard of either term and, if so, to describe his or her experience and knowledge [129]. Guidelines on communicating in the end-of-life setting note that clinicians must "clarify and correct misconceptions" about palliative care, especially emphasizing that such care is not limited to people who are imminently dying [117]. Clinicians should also address the factors that act as barriers to hospice by explaining that the goal of hospice is to die naturally—in the patient's own time, not sooner—and by ensuring that patients and families are fully informed about the prognosis, understand that the physician will be available for care, and know that routine care will continue [98,130].

Clinicians also need to evaluate their own attitudes about the use of curative therapies and hospice. Their interpretation of quality of life, a focus on longer survival rather than better quality of life, a fear of failure, and religious and cultural beliefs may influence their decision making about treatment options for patients near the end of life [131].

Communicating effectively about palliative care and hospice requires basic patient-physician communication skills as well as skills specific to the end-of-life setting. The importance of effective patient-clinician communication across all healthcare settings has received heightened attention over the past several years, as studies have shown a direct relationship between enhanced communication and better patient decision making, patient satisfaction, adherence to treatment, health-related quality of life, and survival [35,67].

Among the most important factors for effective communication across all healthcare settings are knowledge of the language preference of the patient and family; an awareness of the patient's and family's health literacy levels; and an understanding of and respect for the patient's and family's cultural values, beliefs, and practices (referred to as cultural competency) [132,133,134]. These issues are significant, given the growing percentages of racial/ethnic populations. According to U.S. Census Bureau data from 2019, more than 67.8 million Americans speak a language other than English in the home, with more than 16.1 million of them (5.2% of the population) reporting that they speak English less than "very well" [135]. Clinicians should ask their patients what language is spoken at home and what language they prefer for their medical care information, as some patients prefer their native language even though they have said they can understand and discuss medical information in English [136]. When the healthcare professional and the patient speak different languages, a professional interpreter should be used. Studies have demonstrated that the use of professional interpreters rather than "ad hoc" interpreters (untrained staff members, family members, friends) facilitates a broader understanding and leads to better outcomes [137,138]. Using a family member as a translator confuses the role of that member in the family, may involve confidentiality issues, and may lead to a modified message to protect the patient. In addition, individuals with limited English language skills have indicated a preference for professional interpreters rather than family members [139]. Professional interpreters have recommended that clinicians can further enhance the quality of care by meeting with interpreters before discussions of bad news and by explicitly discussing with the interpreter whether strict interpretation or cultural brokering is expected [140].

Knowledge of the family's health literacy is important for achieving treatment goals and good outcomes, yet most individuals lack adequate health literacy. Studies have indicated that as many as 26% of patients have inadequate health literacy, which means they lack the ability to understand health information and make informed health decisions; an additional 20% have marginal health literacy [141,142,143]. Health literacy varies widely according to race/ethnicity, level of education, and gender, and clinicians are often unaware of the literacy level of their patients and family [134,144].

Several instruments are available to test the health literacy level, and they vary in the amount of time needed to administer and the reliability in identifying low literacy. Among the most recent tools is the Newest Vital Sign (NVS), an instrument named to promote the assessment of health literacy as part of the overall routine patient evaluation [145]. The NVS takes fewer than three minutes to administer, has correlated well with more extensive literacy tests, and has performed moderately well at identifying limited literacy [134,144]. Two questions have also been found to perform moderately well in identifying patients with inadequate or marginal literacy: "How confident are you in filling out medical forms by yourself?" and "How often do you have someone help you read health information?" [134]. Clinicians should adapt their discussions and educational resources to the patient's and family's identified health literacy level and degree of language proficiency and should also provide culturally appropriate and translated educational materials when possible.

Cultural competency is essential for addressing healthcare disparities among minority groups [132]. Clinicians should ask the patient about his or her cultural beliefs, especially those related to health and dying, and should be sensitive to those beliefs [146]. In addition, information sharing and the role of decision maker vary across cultures, and the healthcare team must understand the family dynamics with respect to decision making [117]. Clinicians should not make assumptions about the preferences of the patient or family on the basis of cultural beliefs. Even within a single culture or ethnicity, the level of information desired, preferences for treatment, role of other family members in decision making, and goals of care differ among patients and families [40,117]. Clinicians should ask their patients about these issues, as well as other family and social factors and religious or spiritual views [40].

Patients and families have noted that communication about end-of-life care is one of the most important skills for clinicians to have [147]. Experts in end-of-life communication note that physicians have an obligation to discuss medical, psychosocial, and spiritual needs with seriously ill patients in a timely and sensitive manner [148]. In addition, communication guidelines developed by an Australian and New Zealand Expert Advisory Group recommend "all patients with advanced progressive life-limiting illnesses be given the opportunity to discuss prognosis…and end-of-life issues" [117]. At what point in the trajectory of serious illness such conversations should commence is not clear. Studies show that most older adults (older than 65 years of age) prefer to begin a discussion of life expectancy/end-of-life issues with their physician at about six months before anticipated end of life, rather than waiting until weeks or days before [528].

Although the topic is emotionally and intellectually overwhelming for patients and families, they want information. In a systematic review (46 studies), Parker et al. found that patients with advanced life-limiting illnesses and their families have a high level of information needs at all stages of disease [149]. That study and others have shown that the end-of-life issues of most importance to patients are [62,149]:

Disease process

Prognosis for survival for quality of life

Likely symptoms and how they will be managed

Treatment options and how they will affect quality and duration of life

What dying might be like

Advance care planning

Most patients want some discussion of end-of-life issues (including hospice care) at the time a life-limiting illness is diagnosed or shortly thereafter [62,149].

Although many physicians say they avoid discussing end-of-life issues because they are afraid the conversation will destroy the patient's hope, the discussion actually offers many benefits: it makes patients fully informed and thus better able to make decisions about treatment options and care goals; provides patients with an opportunity to achieve closure on life and family issues; allows patients to handle practical matters; and enables patients to carry out advance care planning [35,81,148,150]. As such, the discussion empowers patients, giving them a sense of control over choices [148,150]. Patients who discuss end-of-life issues and goals of care with their clinician also are more likely to receive care that is consistent with their preferences, to enroll in hospice, to complete advance directives, and are less likely to be intubated or to die in an intensive care unit [151,152].

Despite these benefits, studies have consistently shown that few clinicians and patients discuss end-of-life issues or discuss them in a timely manner. Overall, about 25% to 33% of physicians have noted that they did not discuss hospice or end-of-life care with their patients who have life-limiting diseases [128]. In a multiregional study of more than 1,500 people with stage IV lung cancer, 47% had not discussed hospice within four to seven months after diagnosis [153]. Discussions are particularly lacking among people with nonmalignant life-limiting diseases, with 66% to more than 90% of patients or clinicians reporting that they had not discussed end-of-life issues [62,126,154,155].

Even among clinicians who discuss end-of-life care with their patients, the timing is not optimal. Approximately 24% of physicians have noted that they provide hospice information at the time of diagnosis, the point at which this discussion is recommended [128,156]. In a national survey of clinicians caring for people with cancer, most respondents said they would wait until treatment options had been exhausted or symptoms had occurred before discussing end-of-life issues, and many said they would have the discussion only if the patient or family raised the issue [157].

Patients and clinicians should talk about end-of-life issues early to avoid discussing the topic during the stress of exacerbated disease or imminent death. The topic can then be framed as a component of care for all patients with a life-limiting illness [62,117]. According to published guidelines and expert recommendations, end-of-life issues should be discussed when the clinician would not be surprised if the patient died within six months to one year [6,117,148]. As other markers, an end-of-life discussion is generally recommended in the presence of moderate or severe COPD, during evaluation for liver transplantation, and in the presence of stage 4 or 5 chronic kidney disease or end-stage renal disease [62,121,123]. The 2009 ACCF/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and management of heart failure noted that end-of-life care options should be discussed when "severe symptoms in patients with refractory end-stage heart failure persist despite application of all recommended therapies;" the 2013 guideline for the management of heart failure is less clear about the timing of such a discussion [158,159]. The ACCP recommends discussing end-of-life care options when caring for patients with advanced lung cancer [54].

Other indications that should prompt a conversation about end-of-life care are a discussion of prognosis or of a treatment option with a low likelihood of success, a change in the patient's condition, patient and/or family requests or expectations that are inconsistent with the clinician's judgment, recent hospitalizations, and patient and/or family questions about hospice or palliative care [117,148].

Several patient-related and clinician-related factors contribute to the low rate of end-of-life discussions or their untimeliness. Most patients will not raise the issue for many reasons: they believe the physician should raise the topic without prompting, they do not want to take up clinical time with the conversation, they prefer to focus on living rather than death, and they are uncertain about continuity of care and fear abandonment [62,117,148,150]. Clinician-related factors include [81,147,148,160,161]:

Lack of time for discussion and/or to address patient's emotional needs

Uncertainty about prognosis

Fear about the patient's reaction (anger, despair, fear)

Lack of awareness and inability to elicit the concerns of patients and their families regarding prognosis

Lack of strategies to cope with own emotions and those of patient and family

Feeling of hopelessness or inadequacy about the lack of curative therapies (perceived as "giving up")

Perhaps the greatest barrier to end-of-life care discussions is clinicians' lack of confidence in their ability to talk about end-of-life issues, and research has confirmed a low rate of effective communication skills among clinicians, especially with respect to delivering "bad news" [62,81,155,162].

The Australian/New Zealand communication guideline provides several evidence-based recommendations for discussing end-of-life issues, and other experts have offered practical guidance to help clinicians discuss bad news and end-of-life care more effectively [117,163,164,165]. These guidelines and expert recommendations emphasize communication behaviors that patients and families have noted to be most important, such as expression of empathy, acknowledgment and support of emotions, honesty, willingness to listen more than talk, and encouragement of questions [81,117,123,147,149,164].

The most commonly recommended communication approach is SPIKES, a six-step protocol that was developed for delivering bad news in the oncology setting and can be used in other settings [163,164]:

Setting (context and listening skills)

Patient's perception of condition and seriousness

Invitation from patient to give information

Knowledge—explaining medical facts

Explore emotions and empathize as patient responds

Strategy and summary

In establishing the setting, the clinician should ask the patient if he or she wishes to have a family member present for the conversation and should ensure that the discussion takes place in privacy [62,164]. The clinician should also introduce himself or herself to the patient and any others present. With SPIKES, the setting also involves listening skills—the use of open-ended questions, clarification of points, and avoidance of distractions [164].

A 2024 clinical practice feature authored by palliative care experts provides practical guidance to clinicians on navigating and communicating about serious illness and end of life [529]. These experts suggest that rather than a single conversation, the task and the goals of communication over end-of-life issues can be achieved more effectively through a series of conversations conducted over a span of time, focusing on the patient's evolving ability to cognitively and emotionally integrate the likely course and expected outcome of the illness [529]. This approach gives the patient time to integrate prognostic information, adjust emotionally to the impact of disease progression, and then, with growing discernment, express personal preferences for end-of-life care. The tendency of patients to oscillate between expressions of hopefulness and more realistic expectations should be considered a normal and expected part of the process. Patients require time and support to process their hopes and fears, to grieve, and to build coping skills required for living with a terminal illness. By partnering with the patient, demonstrating empathy, and engaging in a continuum of conversation over weeks to months, the clinician (in concert with other members of the care team) can better discern what is most important to the patient and incorporate these goals and values into decisions about therapy, including care at the end of life [529].

Bad news—even when delivered clearly and compassionately—can affect the ability of patients and family members to understand and retain information. To minimize misinterpretation, clinicians should use simple (jargon-free) language and open-ended questions and ask follow-up questions that include the patient's own words [117,164]. Clinicians should also check often to make sure the patient and/or family understands, as research has shown that clinicians tend to overestimate their patients' understanding of end-of-life issues [166]. The discussion should focus on the importance of relieving symptoms and enhancing the quality of life, to avoid having the patient and/or family think that the clinician is "giving up" or abandoning the patient [40,117]. Clinicians should also provide educational resources in a variety of formats (print, Web-based, video, etc.) to address different learning styles.

It was once thought that the ability to communicate effectively was innate and thus could not be taught [164]. However, multiday communication skills training programs have enhanced the skills and behaviors of beginning and experienced physicians and nurses. These programs have improved clinicians' use of more focused questions and open questions, expression of empathy, and appropriate responses to cues [167,168]. Patient-related interventions have also helped to enhance end-of-life discussions. A structured list of questions and the use of individualized feedback forms regarding end-of-life preferences have led more patients to ask their physicians about end-of-life care [169,170].

Most patients say that they want to know their prognosis, and most clinicians believe that patients and families should be told the truth about the prognosis [122,126,150]. However, discussions of prognosis are lacking among clinicians and patients with life-limiting diseases. Across studies and surveys, fewer than half of patients have had a truthful discussion of prognosis [81,108,150]. Many physicians have said they discuss prognosis only when asked by the patient or family [81].

In discussing prognosis, clinicians tend to be overly optimistic, and, although most clinicians believe that they should be truthful, they sometimes withhold the truth, often at the request of a family member [160]. Honesty about the prognosis, with acknowledgment of inherent uncertainty, is needed because patients who are aware of their prognosis are more likely to choose hospice rather than aggressive treatment and to carry out advance directives [31,81,171]. Conversely, patients who are not fully aware of their prognosis tend to overestimate their life expectancy, which can influence decision making about treatment options [129].

As with other end-of-life issues, the prognosis should be discussed when the clinician would not be surprised if the patient died within six months to one year [6,117,148]. For patients with cancer, it is recommended that the prognosis be discussed within one month after a new diagnosis of advanced cancer is made [161]. A guideline from the Renal Physicians Association notes that prognosis should be fully discussed with all patients who have stage 4 or 5 chronic kidney disease or end-stage renal disease [121]. A discussion about prognosis is also recommended before the initiation of such treatments as implantation of a left ventricular assist device, dialysis, and ventilator support [122,150,172,173,174].

Clinicians should carefully prepare for the discussion of prognosis by reviewing the patient's medical record and talking to other healthcare professionals involved in the care of the patient [117]. Because there is variation among patients with regard to their desire for information, clinicians should follow the "ask-tell-ask" approach: ask the patient if he or she is willing to discuss prognosis; if yes, discuss the prognosis and then ask the patient to confirm his or her understanding [62,164]. When discussing prognosis, quantitative estimates are more understandable for patients and family than qualitative ones (such as "poor"), and general timeframes for survival should be given [62,81,164,175]. In addition, clinicians should emphasize that prognosis is determined by looking at large groups of patients and that it is harder to predict survival for an individual [62,121,129,161]. The discussion of prognosis is often not documented in the patient's record but should be [117].

Treatment options and goals of care are other topics that are often avoided in the end-of-life setting. A discussion of the survival benefit of palliative chemotherapy is frequently vague or absent from discussions of treatment options for patients with cancer [176]. In another example, approximately 60% to 95% of physicians involved with the care of patients with heart failure have two or fewer conversations about deactivation of implantable cardioverter defibrillators, and the discussions are usually within the last few days of life [89,177].

Deciding when curative therapy should end is difficult because of the advances made in treatment and life-prolonging technology and the unpredictable course of disease, especially for organ-failure diseases. These factors have led many patients, as well as some clinicians, to have unrealistic expectations for survival [30,178]. Unrealistic expectations are a major contributor to an increased use of aggressive treatment at the end of life. Among more than 900 patients with cancer, those who thought they would live for at least six months were more likely to choose curative therapy than "comfort care" compared with patients who thought there was at least a 10% chance they would not survive for six months [179].

Many studies have demonstrated high rates of aggressive treatment within the last months to weeks of life, with increased rates of hospital admissions, stays in an intensive care unit, use of medical resources, and use of chemotherapy. Goodman et al. found that patients with severe chronic disease near the end of life spent a disproportionate number of days in an intensive care unit and received care from multiple physicians; more than half of the patients saw 10 or more physicians within the last six months of life [55]. Similarly, Sheffield et al. found high rates of admission to the intensive care unit among nearly 23,000 patients with pancreatic cancer, and Unroe et al. found that 80% of more than 229,000 people with heart failure were hospitalized in the last six months of life [180,181]. In the cancer setting, several researchers have reported increased rates of chemotherapy in the last two to four weeks of life [180,182,183]. However, studies to evaluate the benefit of high-intensity treatment near the end of life have consistently found that such treatment offers no survival benefit, decreases the quality of life, and delays the use of hospice [55,80,184,185].

Before discussing treatment options, the clinician should talk to the patient to gauge his or her level of understanding of the disease and prognosis and to explore the quality-of-life factors that are most important [186]. The clinician should frame the conversation to focus on active interventions rather than the end of curative therapy; should focus on the overall care goals; and should discuss options within the context of these goals (that is, does the patient wish to enroll in hospice, enroll in a phase I trial, or be present at a family event?) [81,117]. The discussion should include an explanation of the likelihood of achieving the patient's goals with each option and a comparison of the risks, benefits, and costs of each option, noting the overall lack of benefit of aggressive treatment [187,188]. It is also important to allow the patient and family enough time to express emotion and concerns and to ask questions [117,164,189]. Because frequent exacerbations in organ-failure diseases are usually predictive of a more rapid decline, hospitalizations for disease exacerbation should prompt discussions about changes in prognosis and treatment goals and advance care planning [101,190,191]. Admission to the hospital or intensive care unit should also prompt a discussion of goals and preferences with patients with cancer; this conversation should be documented within 48 hours after admission [161]. The ACCP recommends a discussion of the pros and cons of life-sustaining treatment when caring for patients with advanced lung cancer [54].

When the patient, family, and/or healthcare team do not agree on the benefit/utility of interventions, the clinician should consider consulting with social workers or pastoral care services to help with conflict resolution [187]. In addition, the clinician should explain to patients that the likelihood of insurance coverage for a treatment is low if it is not medically indicated [188].