Dissociation is a natural and normal part of the human experience. An inherent mechanism of the primitive brain, dissociation allows for needs to be met and for protection when one feels especially vulnerable. Understanding the intricacies of dissociation is imperative if a therapist or other helping professional wishes to be as trauma-focused as possible. Trauma and dissociation go hand-in-hand, and this interplay can manifest in ways that are clinically puzzling. However, a main theme of this course is that understanding one's own relationship with dissociation and internal world of parts is an important educational step to working with dissociation effectively.

- INTRODUCTION

- FUNDAMENTALS OF DISSOCIATION

- DIAGNOSTIC PERSPECTIVES ON DISSOCIATION

- THE DISSOCIATIVE PROFILE EXERCISE

- FOUNDATIONS OF WORKING WITH CLINICALLY SIGNIFICANT DISSOCIATION

- PERSONAL METAPHOR AND PARTS WORK

- ADDICTION AS DISSOCIATION

- SUCCESSFUL TREATMENT PLANNING

- CONCLUSION

- RESOURCES

- Works Cited

- Evidence-Based Practice Recommendations Citations

This course is designed for psychologists practicing in a variety of modalities and from a variety of traditions.

The purpose of this course is to equip psychologists with the knowledge and skills that they need to better understand dissociation and its connection to trauma.

Upon completion of this course, you should be able to:

- Define dissociation in a trauma-focused manner.

- Describe the impact and manifestations of trauma and dissociation on the brain.

- Identify common myths about working with dissociative clients in psychotherapy, including historical roots.

- Outline diagnostic criteria for dissociative disorders.

- Describe the Dissociative Profile exercise.

- Describe the screening tools and inventories available for use in clinical settings regarding dissociation.

- Apply personal metaphor and parts work in the care of clients with dissociation.

- Outline the similarities between addiction and dissociation and how they can be framed.

- Discuss key components of successful treatment planning for clients with dissociation.

- Implement approaches for early and later phases of dissociative disorder treatment.

Jamie Marich, PhD, LPCC-S, REAT, RYT-500, RMT, (she/they) travels internationally speaking on topics related to EMDR therapy, trauma, addiction, expressive arts, and mindfulness while maintaining a private practice and online education operation, the Institute for Creative Mindfulness, in her home base of northeast Ohio. She is the developer of the Dancing Mindfulness approach to expressive arts therapy and the developer of Yoga for Clinicians. Dr. Marich is the author of numerous books, including EMDR Made Simple, Trauma Made Simple, and EMDR Therapy and Mindfulness for Trauma Focused Care (written in collaboration with Dr. Stephen Dansiger). She is also the author of Process Not Perfection: Expressive Arts Solutions for Trauma Recovery. In 2020, a revised and expanded edition of Trauma and the 12 Steps was released. In 2022 and 2023, Dr. Marich published two additional books: The Healing Power of Jiu-Jitsu: A Guide to Transforming Trauma and Facilitating Recovery and Dissociation Made Simple. Dr. Marich is a woman living with a dissociative disorder, and this forms the basis of her award-winning passion for advocacy in the mental health field.

Contributing faculty, Jamie Marich, PhD, LPCC-S, REAT, RYT-500, RMT, has disclosed no relevant financial relationship with any product manufacturer or service provider mentioned.

Margaret Donohue, PhD

The division planner has disclosed no relevant financial relationship with any product manufacturer or service provider mentioned.

Sarah Campbell

The Director of Development and Academic Affairs has disclosed no relevant financial relationship with any product manufacturer or service provider mentioned.

The purpose of NetCE is to provide challenging curricula to assist healthcare professionals to raise their levels of expertise while fulfilling their continuing education requirements, thereby improving the quality of healthcare.

Our contributing faculty members have taken care to ensure that the information and recommendations are accurate and compatible with the standards generally accepted at the time of publication. The publisher disclaims any liability, loss or damage incurred as a consequence, directly or indirectly, of the use and application of any of the contents. Participants are cautioned about the potential risk of using limited knowledge when integrating new techniques into practice.

It is the policy of NetCE not to accept commercial support. Furthermore, commercial interests are prohibited from distributing or providing access to this activity to learners.

Supported browsers for Windows include Microsoft Internet Explorer 9.0 and up, Mozilla Firefox 3.0 and up, Opera 9.0 and up, and Google Chrome. Supported browsers for Macintosh include Safari, Mozilla Firefox 3.0 and up, Opera 9.0 and up, and Google Chrome. Other operating systems and browsers that include complete implementations of ECMAScript edition 3 and CSS 2.0 may work, but are not supported. Supported browsers must utilize the TLS encryption protocol v1.1 or v1.2 in order to connect to pages that require a secured HTTPS connection. TLS v1.0 is not supported.

The role of implicit biases on healthcare outcomes has become a concern, as there is some evidence that implicit biases contribute to health disparities, professionals' attitudes toward and interactions with patients, quality of care, diagnoses, and treatment decisions. This may produce differences in help-seeking, diagnoses, and ultimately treatments and interventions. Implicit biases may also unwittingly produce professional behaviors, attitudes, and interactions that reduce patients' trust and comfort with their provider, leading to earlier termination of visits and/or reduced adherence and follow-up. Disadvantaged groups are marginalized in the healthcare system and vulnerable on multiple levels; health professionals' implicit biases can further exacerbate these existing disadvantages.

Interventions or strategies designed to reduce implicit bias may be categorized as change-based or control-based. Change-based interventions focus on reducing or changing cognitive associations underlying implicit biases. These interventions might include challenging stereotypes. Conversely, control-based interventions involve reducing the effects of the implicit bias on the individual's behaviors. These strategies include increasing awareness of biased thoughts and responses. The two types of interventions are not mutually exclusive and may be used synergistically.

#66081: Demystifying Dissociation: Principles, Best Practices, and Clinical Approaches

Dissociation is great puzzlement to many clinical professionals, and often it is through no fault of their own. Many graduate training programs skim over the dissociation part of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and teach that dissociative identify disorder (DID) is extremely rare. Likewise, very little may be included on trauma as well, so the potential association with dissociation is often left unexplored.

Since 2000, there has been more interest and a greater respect for trauma and what is called trauma-informed and trauma-focused care in the clinical professions. The term trauma comes from the Greek word meaning wound, and in its most general sense, it can be defined as any unhealed wound of a physical, emotional, psychological, sexual, or spiritual nature. Like physical wounds, other types of trauma can be experienced in various degrees and levels of intensity. If left unhealed or unprocessed, problems can result that impair an individual's lifestyle or way of being in the world. The most common trauma-related diagnosis is post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), although other clinical diagnoses (e.g., adjustment disorders, reactive attachment disorder, personality disorders) can also have their root in unhealed trauma. As trauma awareness and understanding increases, the field is also realizing that many other diagnoses can have a root in unhealed trauma or their severity can be exacerbated by unhealed trauma.

Some have hypothesized that wherever there is trauma, some aspect of dissociation exists, reflected in the idiom: "If trauma is walking in the door, dissociation is at least waiting in the parking lot." If systems of care are truly going to be trauma-informed (i.e., understanding how unhealed trauma affects the brain and manifests in human distress and behavior), they should also work toward being more dissociation-informed. The hope is that all systems of human services can at least be trauma-informed, yet many clinicians are also in a position to be trauma-focused in their care. Trauma-focused care recognizes the role that unhealed trauma plays in human pathology, and trauma-focused clinicians develop treatment plans using the modalities in which they are trained to actively target sources of trauma and work to bring about resolution[1]. To deliver trauma-focused care, competency in working with dissociation is imperative.

The aim of this course is to equip clinicians with the knowledge and skills that they need to better understand dissociation and its connection to trauma. These knowledge and skills will allow clinicians to be more trauma-informed and trauma-focused in their approach to clinical work. There can be frustration that comes with addressing dissociation, which often originates from myths and misinformation in the field—and teachings on dissociation from some sources that can be too technical.

This phenomenological approach will hopefully empower clinicians to more effectively address dissociation and its various manifestations in clinical practice. Having a sense of dissociation's inherent normalcy in the human experience is a critical aspect of demystifying dissociation. The more one is willing to be introspective throughout this course, as opposed to just reading through the content, the more that can be gained from the course. A series of guided exercises are designed to assist in this process.

Author's Note : The voice with which I am guiding you in this course is one of a trauma and dissociation specialist, trainer, and author. I am also a woman in long-term recovery from a dissociative disorder. I was diagnosed in graduate school when I struggled with internship due to my own unhealed trauma. I endeavor to use my lived experience in concert with modern scholarship about dissociation. Personal stories and experiences will be included throughout the text in italics.

The word dissociation is derived from a Latin root word meaning to sever or to separate. In clinical understanding, dissociation is the inherent human tendency to separate oneself from the present moment when it becomes unpleasant or overwhelming. Dissociation can also refer to severed or separated aspects of self. In common clinical parlance, these separations may be referred to as "parts." Older terminology (e.g., "alters," "introjects") may still be used, although parts is generally seen as more normalizing and less shaming as a clinical conceptualization strategy. Just like all humans dissociate, all humans have different parts or aspects of themselves. In cases of clinically significant dissociation, the separation of parts is typically more pronounced.

The fact that dissociation encapsulates two meanings—the separation from the present moment that can manifest in a variety of ways and the separation from aspects of self—can make learning about and understanding it rather confusing. Consider, however, that the general purposes of dissociation are the same in both constructs: to protect oneself and to get one's needs met. Even the most innocuous example of a person "zoning out" or daydreaming can be seen through this lens. Individuals can go away in their minds to protect themselves from the distress of the present moment, whether that distress shows up as boredom, pain, or overwhelm. Parts, or aspects of self, will either develop over time or fail to integrate with the total self (depending on defining theory) to protect the self or to get needs met, typically needs that primary caregivers are not providing. Underlying theories of dissociation will be discussed in detail later in this course.

One of the leading psychiatric scholars in the treatment of dissociation is Dr. Elizabeth Howell. In her book The Dissociative Mind, she contends [2]:

Chronic trauma...that occurs early in life has profound effects on personality development and can lead to the development of dissociative identity disorder (DID), other dissociative disorders, personality disorders, psychotic thinking, and a host of symptoms such as anxiety, depression, eating disorders, and substance abuse. In my view, DID is simply an extreme version of the dissociative structure of the psyche that characterizes us all. Dissociation, in a general sense, refers to the rigid separation of parts of experience, including somatic experience, consciousness, affects, perception, identity, and memory.

This contention has inspired scores of clinicians. The key to better understanding dissociation truly rests in normalizing it [2,3].

When contemplating dissociation in a general sense, common expressions that come to mind include daydreaming, "zoning out," inability to make appropriate eye contact, escaping to imaginal or fantastical landscapes in the mind, or losing emotional connection to a story being told. Some people will start to yawn, fall asleep, or lose appropriate volume in their voice when distressed. It is very likely that most (if not all) people have done one or more of these things in their lives and may even do them on a regular basis, with or without a clinically significant dissociative diagnosis. Modern-day examples of dissociation include watching too much television, playing on the smartphone, or mind numbingly scrolling through social media. These activities are not dissociative in and of themselves but can be used in a dissociative manner. Even activities used in therapy for emotion regulation, including guided visualizations, can be dissociative because they remove the practitioner from their present surroundings and experiences. While the intention may be solid and indeed very helpful to many people, consider how a person could continue to use such an exercise as an escape instead of as a healthy coping strategy.

In normalizing dissociation, it is useful to look at the construct of adaptive and maladaptive in describing dissociative phenomenon. These distinctions of adaptive and maladaptive are essential to eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy [4]. As constructs, they are similar to the descriptors healthy and unhealthy but with much less of a value judgment. Furthermore, what is adaptive to one person may not be adaptive to another person. What was adaptive at one point in one's life may not be adaptive at other points in his or her life. Consider this example as it relates to dissociation: For a young child growing up in a dysfunctional home, daydreaming was adaptive because it helped him/her survive the perils of this upbringing. However, as an adult, chronic daydreaming can impede one's ability to work and support oneself, keeping one removed from certain realities that need to be faced.

Another example of commonplace dissociation is binge watching television. This practice could be dissociative in a maladaptive sense, but it could also be a needed avenue for self-care that helps a person disconnect from the rigors of work life and day-to-day responsibilities, depending on the relationship and intention with the activity. Clinicians can assist clients in making this distinction only after considering how these patterns show up in their own lives. For example, a clinician may regularly binge watch television and feel like it is a healthy outlet for rest. When the clinician is dealing with intensity in their feelings and life, it is important that they take a break. One could argue that it would be more dissociative, as an avenue to escape feelings, if the clinician dove into doing more work to keep from being present. Work can be tricky for individuals to evaluate, because while it is often an inherently positive activity, it can be taken to a maladaptively dissociative place. A later section of this course will more fully examine the intricate relationship between dissociation and addiction, but briefly, addictive behaviors generally begin as dissociative coping, usually in response to trauma or to distress.

In normalizing dissociation, it is also imperative to examine the notion of parts or aspects of self. Again, this will be more fully explored later in this course, but before starting this activity, take a moment to examine whether or not you relate to having different parts, sides, or aspects of yourself. Many use the common terminology of "inner child," vis-à-vis the more rational, presenting adult. If you have ever used this language, you are already recognizing the construct of parts. Some people, especially those who struggle with addiction, may reference having a "Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde" phenomenon happening within them. Some people will even say that their sadness, anger, or other emotional experience can take on a life of their own, which can also speak to the separation of parts, or that they feel "cut off" from their bodies due to an injury, illness, or other distress. As illustrated in the passage from Dr. Howell, diagnoses like DID or other dissociative disorders refer to a more rigid separation of this very natural part of the human condition [2].

There have been many advances in better understanding trauma and dissociation through a neurobiologic lens. While this section will conclude with some of that research, it is important to obtain a basic understanding of the human brain and how unhealed trauma can impact its functioning. The simplest explanatory model that seems to work the best for clinicians to gain this understanding is the triune model of the human brain, originally developed by psychiatrist Paul MacLean [5]. Many modern scholars (e.g., Bessel van der Kolk, Daniel Siegel) continue to use it as a base of explanation.

The triune brain model espouses that the human brain operates as three separate brains, each with its own special roles—which include respective senses of time, space, and memory [5]:

The R-complex or reptilian brain: Includes the brainstem and cerebellum. Controls instinctual survival behaviors, muscle control, balance, breathing, and heartbeat. Most associated with the freeze response and dissociative experiences. The reptilian brain is very reactive to direct stimuli.

The limbic brain (mammalian brain or heart brain): Includes the amygdala, hypothalamus, hippocampus, and nucleus accumbens (responsible for dopamine release). The limbic system is the source of emotions and instincts within the brain and responsible for fight-or-flight responses. According to MacLean, everything in the limbic system is either agreeable (pleasure) or disagreeable (pain). Survival is based on the avoidance of pain and the recurrence of pleasure.

The neocortex (or cerebral cortex): Contains the frontal lobe. Unique to primates and some other highly evolved species like dolphins and orcas. This region of the brain regulates our executive functioning, which can include higher-order thinking skills, reason, speech, and sapience (e.g., wisdom, calling upon experience). The limbic system must interact with the neocortex in order to process emotions.

Many strategies in the psychotherapeutic professions work primarily with the neocortex. For a person with unprocessed or unhealed trauma symptoms, the three brains are not optimally communicating with each other when the limbic system gets triggered or activated [6]. During periods of intense emotional disturbance, distress, or crisis, a person cannot optimally access the functions of the neocortex because the limbic, or emotional brain, is in control. In essence, a dissociative phenomenon occurs. Blood flow slows to the left prefrontal cortex when the limbic system is triggered to some degree. Thus, a person may be aware of what is happening around them, and yet that disruption or dissociation from the brain's innate totality impedes a person's capacity to process or make sense of it.

Consider these examples that may be familiar to your clinical practice: Have you ever tried to reason with someone in crisis? Have you ever asked someone who has relapsed on a drug or problematic behavior, "What were you thinking?" Have you ever tried to be logical with someone who is newly in love or lust? Attempting any of this is like trying to send an e-mail without an Internet signal. You may have awesome wisdom and cognitive strategies to impart and you can keep clicking send, but the message is not ever going to get through. Moreover, because the activated person has awareness, they may grow increasingly annoyed by persistence, which can activate the limbic responses even further.

Triggers are limbic-level activities that cannot be easily addressed using neocortical interventions alone. If a stimulus triggers a person into reaction at the limbic level, one of the quickest ways to alleviate that pain/negative reaction is to feed the pleasure potential in the limbic system. As many traumatized individuals discover, alcohol use, drug use, food, sex, or other reinforcing activities are particularly effective at killing/numbing the pain. For children growing up in the high distress of a traumatic home, dissociation can become the brain's natural and preferred way to escape the pain. Cultural commentators and scholars have referred to dissociation as a "gift" to the traumatized child for this reason [7].

Dissociation, trauma-related disorders, and addiction are inter-related because dissociation is a defense that the human brain can call upon to handle intense disturbance. People dissociate in order to escape—to sever ties with a present moment that is subjectively unpleasant or overwhelming, stemming from unhealed trauma and its impact. In referencing the triune brain model, dissociative responses—often conceptualized as similar to freeze responses—are even deeper than the limbic brain, taking place in the R-complex or brainstem [8]. This is a testament to their primary, protective quality.

Precise neurobiologic explanations of dissociative phenomenon are still being investigated, and understanding remains incomplete. In their comprehensive review, Krause-Utz, Frost, Winter, and Elzinga summarize that there is a suggested link between dissociative symptoms and alterations in brain activity associated with "emotion processing and memory (amygdala, hippocampus, parahippocampal gyrus, and middle/superior temporal gyrus), attention and interoceptive awareness (insula), filtering of sensory input (thalamus), self-referential processes (posterior cingulate cortex, precuneus, and medial prefrontal cortex), cognitive control, and arousal modulation (inferior frontal gyrus, anterior cingulate cortex, and lateral prefrontal cortices)" [9]. Electrical neuroimaging studies show a correlation between the temporoparietal junction—an area involved in sense of self, agency, perspective taking, and multimodal integration of somatosensory information—and dissociative symptoms, and specific forms of dissociation are connected with brain areas in question [10].

While the neurobiologic implications of dissociation are discussed in detail later in the course, this section has endeavored to give enough base knowledge to understand that trauma and dissociation are inter-related. Basically, dissociation can be described as an inherent mechanism of the human brain that can be called upon to manage distress. The higher the degree and the more intense the trauma, the greater the likelihood that some aspects of dissociation, whether clinically significant or not, can manifest.

Dissociative identity disorder or DID, formerly referred to as multiple personality disorder, can make for fascinating plot points and opportunities for characterization in the media. Unfortunately, these media portrayals have fed perpetuated myths and misconceptions about dissociative disorders that persist in the general public and in mental health professions. In many cases, the media only showcases the most extreme or sensationalized cases of DID [11]. Many clinicians do not realize that their clients are experiencing distress that can be described through the lens of a dissociative disorder because their clients are not presenting with symptoms that look as extreme or severe as the largely fictionalized Sybil or the highly sensationalized portrayal in the 2016 film Split. If clinicians are only using these media portrayals as their point of reference, they may be unnecessarily frightened to treat their dissociative clients, fearing violence, self-injury, or other expressions they may not feel prepared to handle.

Many individuals who dissociate express trepidation about making their condition known to the general public; this can even include fear about coming out to one's partner or one's therapist in fear of judgment. For example, I, a mental health professional active in addiction and trauma care, found "coming out" fully as a person with a dissociative disorder was much scarier than being out as someone in recovery from addiction or being out as a bisexual woman. There was a great fear that I would no longer be taken seriously, especially among professional colleagues, if I was public and open about my experiences.

In 2010, Jaime Pollack started the Healing Together Conference with the goal of providing survivors of complex trauma who identify as having a dissociative disorder a place where they could feel safe enough to share freely. Pollack and others did not feel welcome to share from personal experience as non-clinicians at professional conferences that address trauma and dissociation. Even professional clinicians have experienced a similar sense of disregard for the lived experience. Spaces like Healing Together give people with dissociative disorders from a variety of professional backgrounds a chance to be open and share freely, something that can be a rarity in this world.

There is a variety of myths and misconceptions regularly encountered from clinical professionals and from colleagues who also work as trauma trainers. The most common are the usual fears about people with dissociation acting out and causing harm to self or to others, although clinical experience and evidence suggests that there is no more risk of these behaviors than with other diagnoses [12]. The next set of myths revolves around treatment. There can be a sense that people with clinically significant dissociation, especially DID, do not respond well to treatment and cannot live full and functional lives. In many cases, professionals who hold such myths generally do not have enough grounding in trauma-informed or trauma-focused care to realize the connection between unhealed trauma and the successful treatment of maladaptive dissociation. The other major treatment myth is that for successful treatment of DID or another dissociative disorder to occur, there must be an integration of the various alters or parts into one presenting person. While this is discussed further in the section on treatment, for the time being, please know that many exist functionally and adaptively with the help of their system, and integration in the simplistic sense is never achieved—nor does it need to be.

Many individuals with DID or other dissociative disorders do not shun the word integration, but instead view integration as a healthy sense of cohesion or communication between the system. The term working wholeness may be preferred. However, when working with a client with dissociation, integration can be quite a triggering word, because previous providers may have used the term incorrectly or abusively, making them believe that they must integrate if they want to live a normal life. This can cause upheaval in the system, especially if more vulnerable parts believe they are going to be forced out. Consider this metaphorical comparison: For many years the United States was referred to a "melting pot" of sorts, suggesting the people from various backgrounds came together and blended. This metaphor has garnered criticism because a melting pot suggests that various peoples come together, melt down, and then a single, ideal alloy of an "American" emerges. While some people would like this to be so, it is neither culturally inclusive nor sensitive. An alternate metaphor refers to the United States as a salad or a bowl of stew, indicating that each ingredient brings their own unique flavor while contributing to the whole. This metaphor is also workable when referencing dissociative systems.

Many individuals with clinically significant dissociative disorders do not reach the "integration" debate stage of treatment with their providers because many mental health providers are not willing to take on their cases. Screening out for dissociation and making referrals is very common, leaving many with a message that they are "too much to handle." Often, individuals with dissociative disorders can be prematurely admitted into psychiatric facilities at the mention of self-harm or blanking out time. While clinical professionals should not go against their ethical training if there is a viable intent or a plan articulated for injury to self or others, bear in mind that suicidal ideation and self-harm can be a very normal complex trauma response and part of one's dissociative profile. In some cases, having these feelings normalized and a viable plan for addressing them developed is insufficient. Yet, many individuals who struggle with dissociative issues will not articulate struggles to their providers out of fear of being committed to an institution, which can be an unsafe place for someone with a dissociative disorder. Perhaps the biggest misconception in the mental health field is that dissociation is not real, does not exist, or, if it does, is extremely rare. Not only is this an invalidating experience for individuals, they can end up receiving a host of other diagnoses that result in excessive or improper pharmacotherapy. To understand more about the invalidation factor, please read on to the next section, which discusses historical perspectives on dissociation, how to treat it, and how to diagnose it.

The issue of dissociation and how to diagnose it has been historically shrouded in controversy in the psychological and helping professions, largely because trauma can make people uneasy. Giving people, especially children, trauma-related diagnoses can be an uncomfortable matter. When a child gets a diagnosis like attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or bipolar disorder, the implication and suggestion of the medical model is that something is impaired with their brain. Medications, although often prescribed in concert with some kind of behavioral therapy, are typically emphasized as the solution. However, when a child receives a trauma-related diagnosis, generally someone is responsible—a parent or guardian who exposed them to harm, the school system, or even society at large. This meanders into uncomfortable territory for many people. Further, most medications used in the treatment of dissociative disorders focus on comorbid symptoms (e.g., depression, anxiety); psychotherapy remains the cornerstone of treatment.

Although clinically significant dissociation can develop in adulthood as a response to trauma or other distress, its etiology is usually traced to significant, complex trauma in early childhood. Often, this trauma is of a developmental nature, meaning that it happened when a child was still vulnerable and often involved betrayal by someone they loved or trusted. Useful distinctions between trauma as an incident or event (typically associated with the PTSD diagnosis as presented by the DSM) and complex or development trauma is that complex trauma experiences [13]:

Are repetitive or prolonged

Involve direct harm and/or neglect or abandonment by caregivers or ostensibly responsible adults

Occur at developmentally vulnerable times in the victim's life, such as early childhood

Have great potential to severely compromise a child's development

Initially, even Freud seemed to be convinced of trauma's impact in his early investigation of dissociative phenomenon. As is well-established in the history of psychology, widespread pressure from his influential colleagues resulted in Freud backing down from this hypothesis and instead focusing more on repression and subconscious desires as etiology for mental and emotional disorders. The gendered label of hysteria was put into wide use, a construct that modern trauma scholars now view as a manifestation of complex trauma and dissociation [14]. Much of the early thinking in the field, especially from Pierre Janet, suggested that there is an element of dissociative phenomenon in all mental and emotional disorders, even conceptualizing what would come to be known as schizophrenia through this lens [12]. Other French colleagues of his era proposed similarly.

The dissociative disorders formally debuted in the DSM-III in 1980. The PTSD diagnosis also appeared in that edition as an anxiety disorder, but dissociative disorders were presented as a separate category. Although new to DSM-III, their discussion and inclusion were not new to the field [15]. With every iteration of the DSM since then, up to the current DSM-5, there has been intense debate and scrutiny over the dissociative disorders as being worthy of inclusion. In reality, many leaders of the field, especially those on DSM work groups, openly doubt their existence [16]. The purpose of this course is not to engage in this debate—clearly the position of this course is that dissociative disorders do exist and are potentially more widely prevalent than once thought and reported. However, major medical and psychological groups continue to report that dissociative disorders are extremely rare. This approach to dissociative disorders and resistance to their existence is borne from the same discomfort about trauma and responsibility that Freud encountered in the early days of his work. Although the general phenomenon of dissociation can show up in a wide array of clinical diagnoses, it has been established that unhealed trauma is a major etiologic factor in the development of clinically significant dissociative disorders [17].

Clinicians interested in reading more about the history and debate around dissociation, trauma, and memory are directed to Anna Holtzman's article exploring the "memory wars" in the field of psychology, written in the wake of the Harvey Weinstein trials (Resources). The memory wars refer to decades of debate in the field about the trustworthiness of memory, particularly as it relates to accusations of abuse by survivors of trauma. She discusses the history of the False Memory Syndrome Foundation, founded by the parents of Dr. Jennifer Freyd (a former president of the International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation [ISSTD]). Dr. Freyd accused her parents of abuse and their response was to establish an organization to discredit survivors of abuse.

As long as unhealed trauma continues and people are threatened by its impact or made to feel responsible for it, there is a likelihood that such debate, even in scholarly settings, will continue. The general state of the evidence suggests that not only are dissociative disorders real, the prevalence is higher than previously thought [18].

While the ISSTD and mainstream advocates in the field of dissociation have promoted research and scholarship to prove that dissociation exists, there is a concern by advocates that such a focus may measure the experiences of survivors without adequately including their voices into the advocacy. In the spirit of both/and, this course acknowledges that while scholarship and research are always critical to validate constructs in the mainstream, clinicians can get overwhelmed by trying to study dissociation in this manner. Normalizing dissociation as a human phenomenon and describing how trauma and distress can impact its manifestations should also be a part of the discussion moving forward.

Because dissociation can be explained as a coping device that crosses the line to being a maladaptive symptom for some individuals, it can be contended that trauma-associated dissociation manifests in a variety of clinical diagnoses. In this section, the primary diagnoses categorized in the Dissociative Disorders chapter of the DSM-5 are presented [19]. However, remember that these are not the only places where dissociation may show up diagnostically. Substance use and other disorders, for instance, have a strong dissociative component, and these will be handled separately in another section. There is also a great deal of confusion about where the line exists between distraction (that might be more commonly associated with diagnoses like ADHD, but can also appear in clients with PTSD) and dissociation. Moreover, in the most recent updates to the DSM, there is a new subtype of PTSD that specifically addresses dissociation, which will be included in this section.

For an individual to meet any of the diagnostic criteria that follow, dissociation must not be better explained by a phenomenon like intoxication. Thus, it becomes imperative for clinicians to understand the intricacies of how trauma and dissociation manifest, because many different diagnoses may be on the proverbial table for consideration.

The following sections have been reprinted with permission from The Infinite Mind [20]. These summaries are clinically sound (reflecting what appears in the DSM-5) while also being written in a language that the general public will likely find friendly.

DID, formerly called multiple personality disorder, develops as a childhood coping mechanism. To escape pain and trauma in childhood, the mind splits off feelings, personality traits, characteristics, and memories into separate compartments which then develop into unique personality states. Each identity can have its own name and personal history. These personality states recurrently take control of the individual's behavior, accompanied by an inability to recall important personal information that is too extensive to be explained by ordinary forgetfulness. DID is a spectrum disorder with varying degrees of severity. In some cases, certain parts of a person's personalities are aware of important personal information, whereas other personalities are unaware. Some personalities appear to know and interact with one another in an elaborate inner world. In other cases, a person with DID may be completely aware of all the parts of their internal system. Because the personalities often interact with each other, people with DID report hearing inner dialogue. The voices may comment on their behavior or talk directly to them. It is important to note the voices are heard on the inside versus the outside, as this is one of the main distinguishers from schizophrenia. People with DID will often lose track of time and have amnesia to life events. They may not be able to recall things they have done or account for changes in their behavior. Some may lose track of hours, while some lose track of days. They have feelings of detachment from one's self and feelings that one's surroundings are unreal. While most people cannot recall much about the first 3 to 5 years of life, people with dissociative identity disorder may have considerable amnesia for the period between 6 and 11 years of age as well. Often, people with DID will refer to themselves in the plural [20].

The most common of all dissociative disorders and usually seen in conjunction with other mental disorders, dissociative amnesia occurs when a person blocks out information, usually associated with a stressful or traumatic event, leaving him or her unable to remember important personal information. The degree of memory loss goes beyond normal forgetfulness and includes gaps in memory for long periods of time or of memories involving the traumatic event [20].

Having depersonalization has been described as being numb or in a dream or feeling as if you are watching yourself from outside your body. There is a sense of being disconnected or detached from one's body. This often occurs after a person experiences life-threatening danger, such as an accident, assault, or serious illness or injury. Symptoms may be temporary or persist or recur for many years. People with the disorder often have a great deal of difficulty describing their symptoms and may fear or believe that they are going crazy [20].

Symptoms of unspecified dissociative disorder do not meet the full criteria for any other dissociative disorder. The diagnosing clinician chooses not to specify the reason that the criteria are not met [20].

The other specified dissociative disorder category is used in situations in which the clinician chooses to communicate the specific reason that the presentation does not meet the criteria for any specific dissociative disorder [20].

Many experts have expressed confusion that dissociative disorders were separately categorized instead of being included in the DSM-5-TR chapter grouping trauma- and stressor-related disorders. This may reflect some of the controversy and misunderstanding about dissociative disorders, or a lack of cohesion among the work groups that determine the categories in the DSM.

The chapter of trauma- and stressor-related disorders (which includes PTSD, acute stress disorder, adjustment disorders, reactive attachment disorder, and disinhibited social engagement) does make mention of dissociative symptomology as a potential feature of PTSD. In the DSM-5 version of the PTSD diagnosis, there is a qualifier option of PTSD with predominant dissociative symptoms. Dissociation can play out in all five symptom areas of the PTSD diagnosis, with flashbacks (under Criterion B, intrusion) specifically being described as a dissociative phenomenon. In DSM-5, depersonalization is defined as "persistent or recurrent experiences of feeling detached from, as if one were an outside observer of, one's mental process or body" (potentially an avoidance or negative mood/cognition manifestation) [19]. Derealization is defined as "persistent or recurrent experiences of unreality of surroundings" (potentially a part of the PTSD symptoms of intrusion, avoidance, or negative mood/cognitions) [19]. Although depersonalization and derealization still appear as their own diagnoses in the dissociative disorders category, those diagnoses should be ruled out if PTSD is the better explanation.

This is a gray area to navigate diagnostically, particularly because people struggling with clinically significant dissociative disorders likely meet the criteria for PTSD. With PTSD long being conceptualized as a more event-centric diagnosis that does not accurately encapsulate the depth of complex trauma, this qualifier may be more appropriate for adults who experience a traumatic event not connected to childhood or developmental trauma and develop these dissociative tendencies as a result.

The Dissociative Profile is a process used to evaluate and become aware of one's own tendencies to dissociate, both adaptively and maladaptively, and identify best strategies for directing one's knowing awareness back to the here and now. Therapists and helping professionals should first know their own dissociative profile and by doing this, will help clients to investigate their own [21]. This exercise is not only valuable as an exploratory device—the knowledge gleaned from it can become a valuable part of treatment planning, especially in managing distress that may rise between sessions. This approach is presented prior to discussion of formal psychometric measures with the intent that a general understanding and ability to identify association will help you truly understand these psychometrics and how to use them.

Before engaging in this exercise, please remember that every human dissociates; it is natural and normal. This is not intended to be an exercise in shaming; rather, it should focus on self-inquiry. To engage in the Dissociative Profile exercise, take the following steps, using the sample Dissociative Profile (Table 1) as a guide as needed.

SAMPLE DISSOCIATIVE PROFILE EXERCISE

| My Dissociative Tendencies | What Helps Me Return to Present Moment |

|---|---|

| Daydreaming when I'm bored. This was adaptive when I was a kid; it's how I survived my parents' fighting. Somewhat of a problem/maladaptive now, as it can keep me from paying attention at work or with the kids. | Telling myself to "snap out of it" helps sometimes. This is something I'd like to work on though, because it can be hard to get out of the dream world. |

| Playing too much Candy Crush on the phone. Boredom also seems to trigger this. Doesn't seem to be a problem at the level of addiction or anything; I just know I do it. | Sometimes my eyes get too strained or tired, and that helps me put it down. When I know I have something more exciting/stimulating to work on, I stop. This can include having a conversation with people I enjoy. |

| Saying "it's no big deal" to my own therapist whenever I get too emotional. It's clear that this protected me at home growing up (adaptive), but I know it gets in the way of me doing deeper work | Having my therapist, who I fundamentally trust, gently call me out on it seems to help. When she can guide me through one of her mindfulness exercises encouraging me to notice my body and sit with whatever is coming up, I make steps in the right direction. |

| Problems paying attention when I drive (only sometimes). I'm not sure if this is dissociation or just general distraction. Either way, it does seem to happen when I'm overwhelmed. | Playing music I like in the car helps. I haven't yet taken my therapist's suggestion of taking a few deep breaths before I start driving regardless of how I'm feeling; perhaps I should try that. |

Take out paper or open up a word processing program on your computer. Make two columns. Title the left-hand column "My Dissociative Tendencies," and title the right-hand column, "Strategies for Returning to the Present Moment."

Take as much time as you need to make a list of the ways in which you tend to dissociate—this can be general patterns like "zoning out or daydreaming when I'm bored," or "spending time on Facebook wondering what everyone else is doing." You can take this inventory a step farther by noting if these strategies or behaviors are adaptive, maladaptive, or both (depending on context). Also note, perhaps, how often you engage in these dissociative strategies and if you have knowing awareness about what triggers them (e.g., boredom, emotional pain, overwhelm, conversations with certain people).

After the left column feels complete, go to the right column and beside each item on the left, make some notes about what helps you return to the present moment when you need to. This can be more intrinsic skills (e.g., my mindfulness practice, especially grounding with solid objects), or more externally motivating factors (e.g., hearing my child call out that they need me). Remember that this is not an interrogation; it is simply a true assessment of where you stand. You are also free to be honest and note that you are not sure yet how to draw yourself back to present moment awareness when you get stuck in certain patters.

After finishing your own dissociative profile, take a moment to notice whatever you notice. Is there anything that surprises you? Is there anything you ought to consider sharing with your own therapist, friend, partner, or members of your support system? How can you use what you discover here to assist you in your own personal development and goals or intentions for healing, whatever those may be?

If you are guiding a client through this exercise, be open to debriefing their discoveries with them and developing a plan of action. This can form a solid base for engaging in treatment planning. Moreover, many trauma-focused approaches to therapy stress the importance of having a skills-and-strategies plan for between sessions so the client stays as safe as possible, especially if distress arises in between sessions. Engaging in the Dissociative Profile exercise gives you and your client a general sense of where they stand in terms of existing adaptive skills, and what they need to build for more adaptive engagement with the present moment.

The introduction and first section of this course are designed to provide a foundation to understand the phenomenon of dissociation and how it manifests in the human experience. With this foundation in place, this section seeks to take you deeper into some of the tools, models, and strategies that may be useful in clinical settings to optimally work with dissociation. These may also help to inform treatment planning, which is covered in a later section of the course.

There are a variety of psychometrics and clinical interview guides available for clinicians to help in their identification of dissociation. It is important to keep in mind, as a trauma-focused clinician, many of these devices may be too interrogatory, Use good clinical judgment about whether some of these scales or measures are a good fit for your practice and your clients. They have all played a role in research and helping to validate the existence of dissociative disorders. However, taking a test for a psychometric evaluation can be triggering in its own right and can lead to a sense of confusion in a person's system if they are not properly guided.

At a minimum, clinicians should be familiar with the Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES), developed by Eva Bernstein Carlson and Frank Putnam [22]. This is a screening device, not a pure diagnostic evaluation, so a clinical interview will be necessary in order verify a diagnosis. Even as a screening device, the DES can be a conversation starter and vehicle for investigation, regardless of a person's specific diagnosis. The DES is a 28-item screen in which people are asked to give a general impression of how often they engage in a certain behavior or activity that can be potentially dissociative. Sample items include [22]:

Some people have the experience of driving a car and suddenly realizing that they don't remember what has happened during all or part of the trip.

Some people sometimes have the experience of feeling as though they are standing next to themselves or watching themselves do something as if they were looking at another person.

Some people sometimes find that they become so involved in a fantasy or daydream that it feels as though it were really happening to them.

In the DES-II, people taking the evaluation rate these items by percentage (e.g., this happens to me about 20% of the time). In the DES-III, a basic 0–10 scale is adapted that corresponds with percentages; both versions are approved for clinical use.

To get an average score on the DES-II, you add up the total number of percentages and then divide by 28 (the number of items on the evaluation). Anything above 30% is generally considered to be cautionary for a clinically significant dissociative disorder. Anything greater than 40% is generally considered to be in the range of a clinically significant dissociative disorder. The DES is a starting point for clinicians and clients alike who are not familiar with addressing dissociation. Of course, nothing significant occurs at 30% or 40%; these are simply meant to be a guide for further diagnostic evaluation. One concern is that training programs in specialty therapies that use the DES to screen for dissociation can promote fear. For example, in the EMDR therapy community, some programs can promote the idea that people with a DES score greater than 30% are not appropriate candidates for EMDR or other types of deep trauma work. This is another of the myths and misconceptions. If the DES is greater than 30%, precautions should be taken and therapists can use the information gleaned from the DES to obtain a better sense of a person's relationships to dissociative responses based on their trauma.

After a client takes the inventory (preferably in office, so a therapist is available if they have any questions or concerns or get triggered), review the high item responses with them (greater than 30% to 40%) and ask them to talk more about when they started noticing that response over the course of their life and how it plays out for them presently. You may also ask if they notice how the specific behavior helps them to cope in any way. This information is more valuable, both in diagnosis and treatment planning (which also includes between-session safety planning) than any specific number.

In the spirit of getting to know one's own dissociative profile and relationship with dissociation, clinicians should take the DES for themselves first. It can be scored, but it may be more valuable to investigate how some of the higher scoring items fit into the Dissociative Profile exercise completed in the previous section. Other psychometrics in use clinically include:

Structured Clinical Interview for Dissociative Disorders (SCID-D)

Dissociative Disorders Interview Schedule (DDIS)

Multidimensional Interview of Dissociation (MID)

Many of these tools are available online (Resources).

One of the classic concepts and articles in the field of dissociation studies is Fraser's Dissociative Table Technique. This concept was key to introducing the idea that a person with dissociative parts could get to know their system and how the various parts inter-relate with each other. Publication of Fraser's seminal article led to the popularization of the "conference table" metaphor for individuals with dissociation mapping out their parts and how they inter-relate. Fraser introduces a variety of other metaphorical possibilities as well for this mapping, with an emphasis that the table metaphor is only one part of his larger technique [23,24]. In his core article, he discusses the use of the following approaches that make up the Dissociative Table exercise [23]:

Relaxation imagery: Using guided imagery as preparation and resourcing.

Dissociative table imagery: Presented as the most important component of the exercise, this involves using the principle of imagery for a client to begin seeing their internal system take seats around a table (with modifications if tables feel unsafe). He credits this as a Gestalt-based technique.

Spotlight technique: Sets up the idea of the spotlight being shined on the alter (or part) that is directly speaking to the therapist (with modifications if the light feels unsafe).

The middleman technique: Establishes a system of communication between the alters or parts whereby one can speak on behalf of several others. This technique addresses the concept of co-consciousness, referring to two or more parts/alters sharing consciousness at the same time (not blacking out, "going away," etc.).

Screen technique: A distancing technique whereby distressing memories can be viewed as if they are on a screen in the same room as the table.

Search for the center ego state (inner self-helper): Establishing or revealing what may be referred to as the "core self" of the presenting self that has the strongest overview/sense of the entire system. This may be referred to as the presenting adult or the core self. Some controversy exists over whether or not it is necessary for some dissociative systems to have a center ego state.

Memory projection technique: Another technique for furthering communication between the various alters/parts and their memories, using the various parts to bring in resources as other states may work to process or heal other memories on the screen.

Transformation stage technique: A technique that can be used to transform a person's relationship to the memory and how they see themselves in the memory in terms of time, space, and age.

Fusion/integration techniques: Although there is some controversy and trigger potential around integration in these techniques (as discussed previously), Fraser ultimately seems to be an advocate of integration using some of these fusion points as stepping stones.

The original article is a vital source of information for those interested in working more deeply with dissociation (Resources). Although it has its flaws, Fraser's Table can be a good starting point for clinicians who want direction on how to work with a system. The piece is also important because Fraser advocates for the reality of dissociation and how to work with it. He also addresses one of the controversies around dissociation—the idea that the therapist inserts parts or alters and their memories. While clinicians can guide people into identifying their own system and understanding how it works, it is vital that they do not force agendas and ideas on a person about what is happening. In EMDR therapy, there is a concept of therapists staying out of the way as much as possible and viewing themselves as facilitators or guides. Such an attitude is very helping, regardless of orientation, in helping people work with and identify their parts.

While Fraser's Table is arguably one of the most popular approaches in the first wave of dissociation studies following the formal introduction of dissociative disorders into the DSM-III, the Theory of Structural Dissociation, developed by Onno van der Hart, Ellert Nijenhuis, and Kathy Steele, has become the focus of dissociation studies in the 21st century. Many trauma-focused professionals are advocates of this theory because, at its heart, it is nonpathologizing, positing that everyone is born with a fragmented or dissociative mind [25]. This is normal for infants, who get their various needs met in the absence of speech, language, or a more developed neocortex. Healthy development is defined by needs being consistently met engendering a natural integration of the personality structure. Yet, in the presence of unhealed trauma, disorganized attachment or developmental distress, a natural separation can remain.

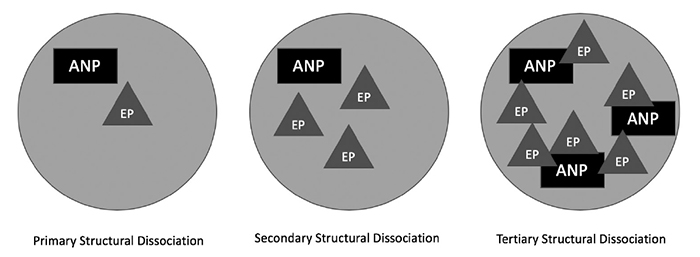

The two main terms used in the Theory of Structural Dissociation are apparently normal personality (ANP), which is similar to Fraser's idea of the center ego state, and emotional part or personality. Emotional parts remain to protect or to meet a need, and some systems contain a more complicated interconnection of emotional parts and ANPs than others. While this is a bit of an oversimplification of how structural dissociation plays out systemically, it gives people new to this theory a good frame of reference. The model also makes use of the terms primary structural dissociation (which is more likely to be used in relation to PTSD and other trauma-related disorders), secondary dissociation (mainly related to personality disorders, dissociative disorders other than DID, and complex PTSD or developmental trauma), and tertiary dissociation (classically presented as DID). Figure 1 provides a visual presentation of how this may play out.

The Theory of Structural Dissociation is certainly not without criticism. For example, psychiatric leader in the field of dissociation Dr. Colin Ross proposed an extensive modification to the theory. In his modification, Ross proposes that an emotional part does not have to be separate entities in and of themselves; instead, they can hold a fragment or experience like a thought, feeling, memory, or sensation. In this modification to the model, he expands on the Janetian idea that many disorders can be viewed through the lens of dissociation and that the idea of parts can be used as treatment conceptualization for conditions like substance use disorders and compulsive behaviors.

The theory of structural dissociation is a step in the right direction, and Ross' modifications expand the scope of what is possible and gives more permission to modify, which is essential in any facet of trauma-focused care. If rigidly interpreted, the original model is too inflexible, which is dangerous when applied to the phenomenon of systems that is fundamentally fluid and unique to the individual. Another consideration is the potentially offensive use of the adjective "normal" to describe the core self or presenting adult (ANP). This speaks to a reality of care in helping people to identify and to get to know their system; part of this is helping them to identify the terminology that best works for them and their understanding.

In working with clients with dissociation and identifying your own dissociative tendencies, clinicians can lean into the metaphorical possibilities that people can develop as they endeavor to understand their systems and how they work. Fraser's metaphors are a solid start, and the circles and shapes often used to represent structural dissociation are a good jumping off point. However, because creativity and expression are part of what defines the dissociative mind, using more creative metaphors may be better serving to you and to your clients [21].

Consider Ms. M, a client with an unspecified dissociative disorder. Ms. M is aware of a very defined inner world before coming into therapy, an inner world that she describes as a series of eight parts, all with their own name and purposes. Ms. M is delighted and surprised when her new therapist allows her to reference her parts and talk this way about them, as previous therapists discouraged her from using this language and conceptualization to refer to herself. "Show up as the adult," is something she heard more times than she ever cared to count.

The therapist asks Ms. M if she sees her parts in any specific way, and she answers immediately—"Yes, I see them as a dollhouse!" She goes on to describe that each part has their own room, and that when she wants them to come together and have a discussion, she senses that they all meet in the living room for a gathering of sorts. They use this mapping of her system as vital information in developing her treatment plan and approach. Interestingly, Ms. M did not require assistance in developing this metaphor—it was already innate within her, and she just needed permission and space to speak it. Other clients may require more of a guide or some examples to help them map out their parts and how they interplay within a system. This can be a creative exploration to understanding the self whether or not a person has a clinically significant dissociative disorder. Other metaphorical possibilities include:

A car or van

A circle of people, like you see in group therapy or a 12-step meeting

Balloons

Bouquet of flowers

An orchestra or band

Salad or stew

Mosaics

Hindu gods

Gathering of saints

The elements (i.e., earth, air, water, and fire)

Keys on a ring

Movie references (e.g., the houses used in Harry Potter, ensemble pieces like Star Wars, Guardians of the Galaxy, Black Panther, orThe Wizard of Oz)

Other pop culture references (e.g., television shows, songs on a playlist, characters from literature)

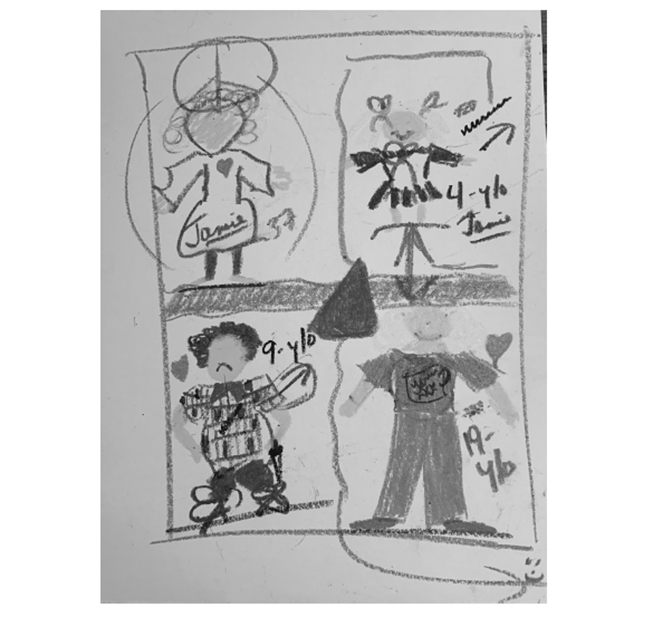

Figure 2 is an example of how visual representation or other art work can be used to help a person identify the parts of their system and how the inter-relate.

The example in Figure 2 is from my own healing journey. I find the car or the van to be a particularly useful metaphorical construct for helping me (and others) to understand my system and how the parts inter-relate. The way I know myself, my presenting adult or core self is always driving the car. However, if the various parts that ride along with me— who I call 4, 9, and 19 (representing their ages)—are not getting their needs met or are not being listened to, they can start to act out or withdrawal in the car. For me, they usually do things like tap on my shoulder, pull my hair, or scream until I pay attention to them and what they are trying to tell me. During an earlier period of my own healing, when the 4-year-old state had some serious healing work to do, it literally felt like she was sneaking behind me and covering my eyes with her hands just so I would pay attention to her. Clearly that caused some distress in my life, and I was not able to return to a place of equilibrium and optimal functioning until I engaged in therapeutic work that helped to heal the four-year-old, the actual age when my own traumatic experiences intensified. If you have ever been on a road trip with children, you know that keeping the peace can be a delicate balance. That is what my mind feels like when I am not listening to the consensus of my system. My 9-year-old part, for instance, is now good about telling us when we need to pull over and take a break. Although she originally developed as the part that held destructive behaviors like self-injury and suicidal thoughts, she has become the voice, in our healing, that tells us when we need to take care of ourselves. I have also used my 19-year-old part as a middle-woman of sorts (using the Fraser term) to broker peace between the 4 and 9 year old, who can annoy each other. Although 19, who has a babysitter quality, can be good at this, she has recently become very good at telling me when this tires her out too much and she needs her own space. Interestingly, I experienced a series of traumatic losses and also crossed the threshold into active addiction at 19 years of age, which is why she emerged or stayed around as a separate emotional part in my system. In healing, I have come to appreciate 19 as a strong, rebellious spirit who started to question the norms in which she was raised. Though this naturally brought about some distress for her, healing from this distress has helped to heal our whole system.

I hope this personal look at a few metaphorical possibilities has been helpful to you as you begin to conceptualize systems and parts work.

Some clients will develop names for their parts, some will refer to them just as numbers or ages (as in the related experience), and others will refer to them just by descriptive qualities (e.g., my angry side, my soft side, the shame part, the inner child). Before beginning work with people using Fraser's Table, mapping in the spirit of structural dissociation theory, or one of these more creative metaphors, clinicians are encouraged to first do some mapping of their own internal system. In essence, this is an important continuation of the Dissociative Profile exercise.

To do this, first spend some time brainstorming, preferably writing down, how you see the parts of yourself. Remember that if you are stuck and nothing you are reading here resonates, you can use the basic presenting adult/inner child construct. If that is the case, how do you see them inter-relating? Staying with the idea of the table, perhaps you simply imagine them sitting down to interact over a cup of tea (or maybe your adult drinks the tea and you pour lemonade for the inner child).

Using paper and whatever basic art supplies you might have on hand (or even just a pen or pencil), begin to map how you see your internal system inter-relating. Doing this exercise does not diagnose you with a dissociative disorder. We all have parts, and seeing ourselves in this way can be a useful strategy for conceptualizing.

This exercise is not about being an outstanding artist—you are not being graded or judged. Simply think of this as drawing out a rudimentary map (and for that matter—the "map" itself could be another useful, metaphorical example). Some people like to use the idea of a circle (e.g., in some cases using plain white paper plates) as the backdrop for how they map out their system.

Take as much time as you require to complete the exercise. When you are though, consider journaling/writing some impressions or sharing them with a friend or colleague. What have you learned about how the various parts of your system inter-relate? Where is there room for a greater sense of communication or understanding in your system? Are there any blocks that are apparent to communication, cohesion, or wholeness?

An exercise like this offers creative, client-centered insight into working with parts or mapping a system, and it may certainly be used with clients, especially in the early stages of working together. What you learn here can phenomenally inform your strategies for treatment planning, which is covered in a later section. Perhaps you are already beginning to understand that what works for one part of the system for resourcing and healing may be different than what other parts in the system require. This will be valuable information for moving forward with treatment.

The addiction treatment field is making steady steps toward becoming more trauma-informed, but a deficit in professionals' ability to identify signs and symptoms of dissociation persists [26]. This is a problem, especially because of the strong interplay between dissociation and addiction. Many clients will be unaware of dissociative symptoms experienced in childhood because drinking and using drugs can become their dissociative outlet in adulthood. Specific dissociative symptoms (e.g., "zoning out" at work or when emotionally overloaded) can develop in sobriety, and will require trauma-focused treatment. This phenomenon is relatively common in recovery circles, but it is often written off as "the pink cloud of recovery is passing," or "things are getting tough." When a person has a difficult time staying sober after getting sober, unhealed trauma is usually the culprit, and dissociation is a possible manifestation [6,26].

In an article on the importance of dissociation-informed treatment, several other dissociative behaviors that manifest clinically but that professionals often fail to identify were identified [26]. They included clients struggling to pay attention in group, at 12-step meetings, or during lectures; a client changing tone (e.g., "It's like I'm suddenly speaking to a 5 year old") when something distressing comes up in sessions or in group; and other manifestations of blocking or resistant client behaviors. When a client gets belligerent or angry, this may be a sign of dissociation. In some clients, these types of behaviors could be a part speaking out to protect the system or to get a need met.

The Addiction as Dissociation Model posits that addiction is a manifestation of dissociation. When children grow up in traumatizing, invalidating, or high-stress environments, the natural tendency is to dissociate in order to get needs met and protect themselves. If this happens frequently, the systems bond to this dissociative experience. At a later point in life, when chemicals or other reinforcing behaviors are introduced as possibilities, the chemical impact enhances the potency of an already familiar experience [27].

The term addiction is controversial in the modern era, because many critics feel that term is stigmatizing and not adequately trauma-informed [28]. To address this, the Addiction as Dissociation Model defines addiction as "the relationship created between unresolved trauma and the continued and unchecked progression of dissociative responses" [27]. In presentations where primary addiction treatment has failed to address trauma, dissociative experiences may produce a dissociative disorder or clinically significant symptoms of dissociation. Similarly, if dissociation in trauma has not been treated accordingly, addiction can often manifest [29]. The model contends that addiction develops in relation to trauma and dissociation, because trauma (cause) produces dissociation (effect).

According to the dissociation in trauma concept, there is a "division of an individual's personality, that is, of the dynamic, biopsychosocial system as a whole that determines his or her characteristic mental and behavioral actions" [29]. This distinction can also be seen in Waller, Putnam, and Carlson's taxometric analysis regarding nonpathologic and pathologic (e.g., adaptive and maladaptive) dissociative traits, of which "dissociation in trauma" would be represented by the latter [30]. Dissociation is what creates safety and ultimately pain relief in the moment of need. Trauma deeply impacts a person's psyche—extreme limits are pushed, and extreme reactions become necessary.

Mergler, Driessen, Ludecke, et al. examined the relationship between the PTSD dissociation subtype (PTSD-D) and other clinical presentations [31]. In a sample of 459 participants, the PTSD-D group demonstrated a statistically significantly higher need for treatment due to substance use problems, in addition to higher current use of opioids/analgesics and a higher number of lifetime drug overdoses. They ultimately concluded that PTSD-D is related to "a more severe course of substance-related problems in patients with substance use disorder, indicating that this group also has additional treatment needs" [31]. Such a connection seems like clinical common sense, but it has not been fully explored in the treatment literature.

Table 2 illustrates the tenets of the Addiction as Dissociation Model, a cohesive presentation of what exists in the literature on the inter-relation and interplay of trauma, addiction, and dissociation. While the literature clearly exists to support such a model, the model represents the first cohesive discussion of their interplay. The implications for treatment, which are summarized here and continued into the next section, are various.

ADDICTION AS DISSOCIATION MODEL

| Foundation: The Human Brain | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| The Impact of Trauma-Dissociation-Addiction | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Treatment and Healing Implications | ||||||||

|

Case conceptualization that respects addiction as dissociation and the related interplays between trauma, dissociation, and addiction acknowledges that addictive behavior is a dissociative response that can elicit its own continued trauma. Moreover, case conceptualization in this model defines and validates the symptoms of addiction accurately and sees the survival behavior as adaptive. This model presents how trauma and dissociation become addictive (i.e., highlights the endogenous neurochemical processes that create the dependent bond in dissociation/addictive processes), how unconscious re-enactments and feedback looping are foundational to recidivism, and provides the justification for comprehensive treatments to directly incorporate a memory reconsolidation phase.

This contention does not suggest that time-honored interventions for treating addiction should be abandoned. However, these interventions should be fortified based on the light of evolving knowledge about trauma and dissociation [6]. Solutions worth highlighting include developing the power of nonjudgmental support communities and the importance of cultivating daily practices that lead to lifestyle change. As such, the community of mutual help fellowships also benefits from an understanding of trauma and dissociation. Peer support services and fellowships like Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, Al-Anon, and Adult Children of Alcoholics can provide a safe place to discuss solutions, as long as there is a reasonable degree of trauma-informed ethics in the culture of the meeting.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT), and Seeking Safety (SS) are often used in the treatment of addiction. There is an evidence base for their use in successfully treating addiction and other substance use disorders [32]. Yet with the public health crisis of addiction continuing, it is clear that more should be done to address the root of the problem—trauma. Each of these approaches lacks a comprehensive definition of addiction, a conceptualization of where addiction fits into the psychopathology of mental health disorders, and an appreciation for how addiction is experienced as traumatic and how addiction relates to trauma and dissociation. Furthermore, they do not directly incorporate memory resolution or memory reconsolidation as an aspect of treatment.

Treatments like DBT and SS specifically offer PTSD symptom management, and they can be helpful to clients in early stages of treatment for addiction and for individuals with clinically significant dissociative disorders. However, they are not comprehensive therapies if one appreciates addiction as a manifestation of dissociation, as the memory resolution phase of the three-stage consensus model of trauma treatment is absent [33]. Clinicians who mainly practice CBT are advised to incorporate trauma-focused CBT (TF-CBT) to work with both trauma and addiction memory. While processing the narrative or explicit memories is important, having ways to process the physical aspects of trauma is necessary for adaptive resolution and to produce personal transformation [34,35,36,37].

Ultimately, incorporating trauma resolution and memory reconsolidation therapies is essential to bring about healing of the root of the problem, not just the symptoms. Memory reconsolidation is based on the belief that the brain, through a process of memory retrieval and activation, can delete unwanted emotional learning [35]. Progressive counting, emotional coherence, brainspotting, deep brain reorienting, and EMDR therapy provide more direct ways of resolving traumatic/addiction memories [4,35,37,38,39].

No instant cure or approach to psychotherapy exists for healing trauma, dissociative disorders, or any mental health conditions. In fact, if a professional claims that they have the curative answer for working with trauma and dissociation, proceed with caution. Particularly when working with dissociative systems, the answer to successful treatment rests in finding the approach or series of approaches that works best for that client to achieve their treatment goals. With the intricacies of parts and dissociative systems, it is very likely that a variety of tools and approaches will be necessary, as what works for one part may not resonate with another. This is where being an eclectic or integrated therapist, albeit with a solid understanding of trauma, will serve best.